In 1835, U.S. officials traveled to the Cherokee Nation’s capital in Georgia to sign a treaty forcing the Cherokees off their lands in the American South, opening them to white settlers. The Treaty of New Echota sent thousands on a death march to new lands in Oklahoma.

The Cherokees were forced at gunpoint to honor the treaty. But though it stipulated that the Nation would be entitled to a nonvoting seat in the House of Representatives, Congress reneged on that part of the deal. Now, amid a growing movement across Indian Country for greater representation and sovereignty, the Cherokees are pushing to seat their delegate, 187 years later.

“For nearly two centuries, Congress has failed to honor that promise,” Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, said in a recent interview in the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, in eastern Oklahoma. “It’s time to insist the United States keep its word.”

The Cherokees and other tribal nations have made significant gains in recent decades, plowing income from sources like casino gambling into hospitals, meat-processing plants and lobbyists in Washington. At the same time, though, those tribes are seeing new threats to their efforts to govern themselves.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

A U.S. Supreme Court tilting hard to the right seems ready to undermine or reverse sovereignty rulings that were considered settled, while new state laws may affect how schools teach Native American history. And tribes are embroiled in a caustic feud with Oklahoma’s Republican governor — despite his distinction as the first Cherokee citizen to lead the state — that has helped to make his re-election bid next week a tossup.

Amid such challenges, the Nation is trying to cobble together bipartisan support for its delegate, who, if seated, would resemble the nonvoting House members representing several territories and the District of Columbia. Such delegates cannot take part in final votes, but can introduce legislation and serve on committees.

Kimberly Teehee, nominated in 2019 for the delegate position, said the role would open a new space for Indigenous representation. “We have priorities that are similar to other tribes when it comes to deployment of dollars, accessing health care, public safety, preserving our culture,” Ms. Teehee said. “This treaty right allows us to have a seat at the table.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The Cherokee Nation has about 430,000 citizens, Ms. Teehee said, which is more than the combined population of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands, all of which have their own delegates in Congress.

Tribal nations across the United States are closely following the debate, eyeing the possibility that it could set a precedent. The Choctaw Nation may also have the right to a delegate under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830, signed before its removal from what is now Mississippi. Similarly, the Delaware Nation’s treaty with the United States in 1778 could allow its members a delegate.

“I think you’ll see a significant outcry from the rest of Indian Country saying, ‘We want one, too,’” said M. Alexander Pearl, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma and a citizen of Chickasaw Nation. “And I think that they’re right.”

Still, the Cherokees could face headwinds in the deeply divided House. Ms. Teehee is a Democrat and former adviser to President Barack Obama. A spokesman for Representative Kevin McCarthy, the House Republican leader, did not immediately respond to an inquiry about the Cherokees’ effort.

Mr. Cole, the Oklahoma Republican, has said that he doesn’t object to seating the delegate, but he also noted that “there’s a lot of challenges to it,” including the question of dual representation in the House.

“There’s a lot of people that will say, ‘Well, that delegate’s chosen by a council, not by a general election,’” Mr. Cole said this year. “And Cherokees then get two votes: your vote for a council member and their vote for the congressman of their own district, so they sort of get to two bites of the apple.”

A report by the Congressional Research Service raised other potential legal issues, including the possibility that the delegate provision would not apply now that Oklahoma is a state, not Indian Territory.

The debate is lifting the veil on one of the most contentious periods between the United States and Indigenous peoples, when about a quarter of the 16,000 Cherokees who walked what’s known as the Trail of Tears died on their way to Oklahoma. “This is a chance to finally reckon with ethnic cleansing, and massive and catastrophic loss of life,” said Julie Reed, a historian and Cherokee Nation citizen who teaches at Penn State University.

The push for a delegate after nearly two centuries also reflects the wider effort by Native Americans to exercise self-governance in ways that would have been unrecognizable to previous generations in Indian Country, a federal designation for land under tribal jurisdiction.

Native candidates have recently won congressional seats in states ranging from Alaska to Kansas. Some tribes are buying back ancestral lands. And Indigenous nations are expanding their own criminal justice systems across the country.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“The 1950s was the lowest point of Indian sovereignty,” said Robert J. Miller, a citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and a law professor at Arizona State University, citing the failed attempt by the U.S. government to disband tribes and relocate their members to cities. “The comeback has been incredible.”

Such breakthroughs, however, are taking place against the backdrop of other challenges, including those before the Supreme Court. In one ruling in June that upended longstanding precedents, the justices expanded the power of state governments over tribal nations.

The 5-4 ruling, which allows states to charge non-Indians for crimes committed against Indians on tribal land, stunned experts on Native American law and weakened a major decision from just two years before that had established the authority of tribal or federal courts on Indian land. (Tribal courts would retain authority over Native Americans who commit crimes on the reservation.)

Another case set to be heard by the court this year, challenging a 1978 law giving Native Americans preference in adopting Native children, could be just as unsettling. The law was intended to put an end to policies allowing Native children to be forcibly taken from their homes and placed by child welfare agencies in non-Native homes.

Plaintiffs, including the State of Texas, argue that the law created a system illegally based on race. But many tribal nations, including the Cherokees, have lined up against the challenge.

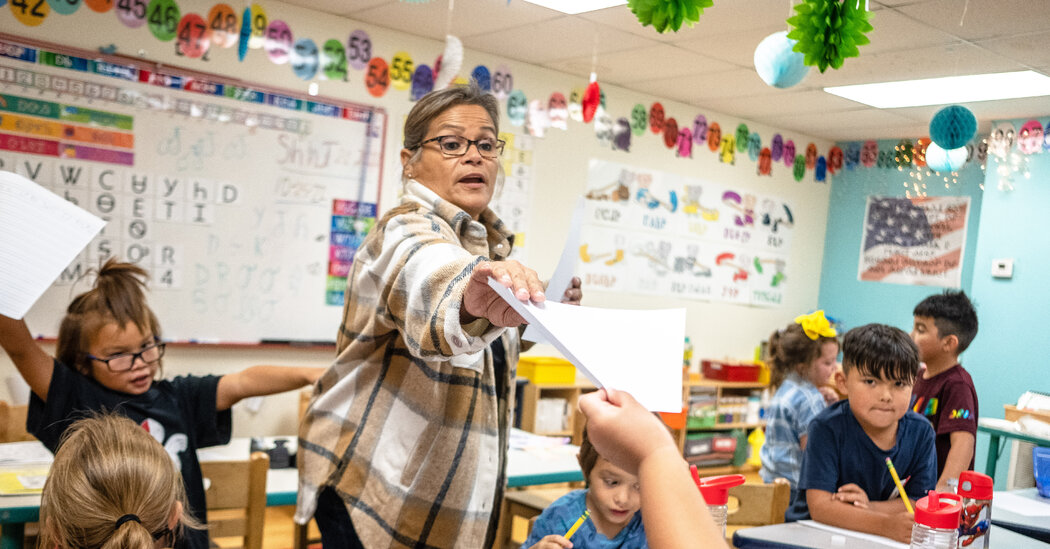

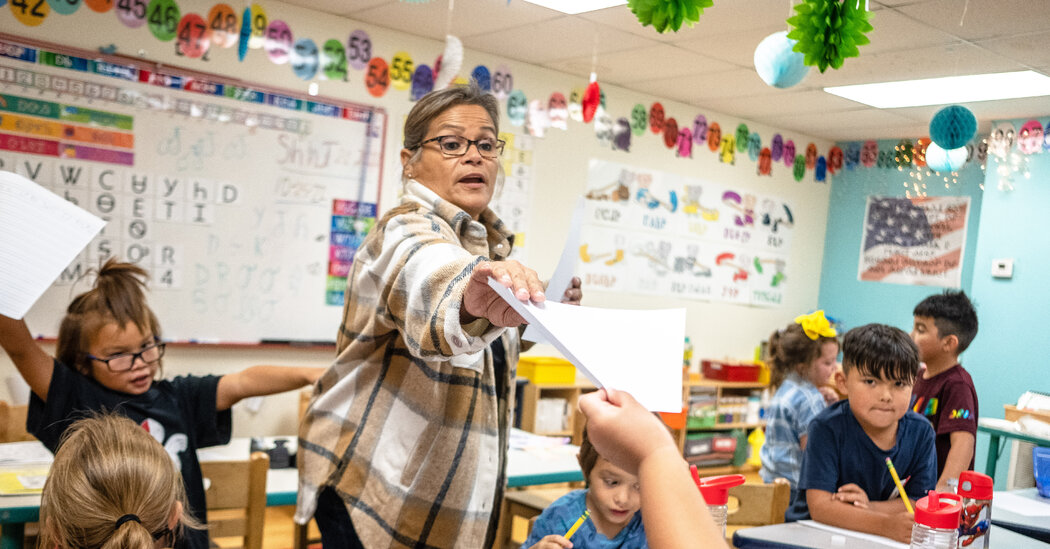

New measures at the state level are also flaring tempers, including an Oklahoma law banning schools from teaching material that could cause students discomfort or psychological stress because of their race.

www.nytimes.com

www.nytimes.com

The Cherokees were forced at gunpoint to honor the treaty. But though it stipulated that the Nation would be entitled to a nonvoting seat in the House of Representatives, Congress reneged on that part of the deal. Now, amid a growing movement across Indian Country for greater representation and sovereignty, the Cherokees are pushing to seat their delegate, 187 years later.

“For nearly two centuries, Congress has failed to honor that promise,” Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, said in a recent interview in the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, in eastern Oklahoma. “It’s time to insist the United States keep its word.”

The Cherokees and other tribal nations have made significant gains in recent decades, plowing income from sources like casino gambling into hospitals, meat-processing plants and lobbyists in Washington. At the same time, though, those tribes are seeing new threats to their efforts to govern themselves.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

A U.S. Supreme Court tilting hard to the right seems ready to undermine or reverse sovereignty rulings that were considered settled, while new state laws may affect how schools teach Native American history. And tribes are embroiled in a caustic feud with Oklahoma’s Republican governor — despite his distinction as the first Cherokee citizen to lead the state — that has helped to make his re-election bid next week a tossup.

Amid such challenges, the Nation is trying to cobble together bipartisan support for its delegate, who, if seated, would resemble the nonvoting House members representing several territories and the District of Columbia. Such delegates cannot take part in final votes, but can introduce legislation and serve on committees.

Kimberly Teehee, nominated in 2019 for the delegate position, said the role would open a new space for Indigenous representation. “We have priorities that are similar to other tribes when it comes to deployment of dollars, accessing health care, public safety, preserving our culture,” Ms. Teehee said. “This treaty right allows us to have a seat at the table.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The Cherokee Nation has about 430,000 citizens, Ms. Teehee said, which is more than the combined population of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands, all of which have their own delegates in Congress.

So far, the Nation has drawn backing from Native American leaders across the country, as well as measured support from members of Oklahoma’s congressional delegation, including Representative Tom Cole, a Republican and member of the Chickasaw Nation.

The House Rules Committee, led by Mr. Cole and Representative Jim McGovern, a Democrat from Massachusetts, is expected to hold a hearing on the Cherokee delegate in mid-November. Even if control of Congress changes in next week’s midterm elections, that could open the way for a vote before the end of the year.Tribal nations across the United States are closely following the debate, eyeing the possibility that it could set a precedent. The Choctaw Nation may also have the right to a delegate under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830, signed before its removal from what is now Mississippi. Similarly, the Delaware Nation’s treaty with the United States in 1778 could allow its members a delegate.

“I think you’ll see a significant outcry from the rest of Indian Country saying, ‘We want one, too,’” said M. Alexander Pearl, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma and a citizen of Chickasaw Nation. “And I think that they’re right.”

Still, the Cherokees could face headwinds in the deeply divided House. Ms. Teehee is a Democrat and former adviser to President Barack Obama. A spokesman for Representative Kevin McCarthy, the House Republican leader, did not immediately respond to an inquiry about the Cherokees’ effort.

Mr. Cole, the Oklahoma Republican, has said that he doesn’t object to seating the delegate, but he also noted that “there’s a lot of challenges to it,” including the question of dual representation in the House.

“There’s a lot of people that will say, ‘Well, that delegate’s chosen by a council, not by a general election,’” Mr. Cole said this year. “And Cherokees then get two votes: your vote for a council member and their vote for the congressman of their own district, so they sort of get to two bites of the apple.”

A report by the Congressional Research Service raised other potential legal issues, including the possibility that the delegate provision would not apply now that Oklahoma is a state, not Indian Territory.

The debate is lifting the veil on one of the most contentious periods between the United States and Indigenous peoples, when about a quarter of the 16,000 Cherokees who walked what’s known as the Trail of Tears died on their way to Oklahoma. “This is a chance to finally reckon with ethnic cleansing, and massive and catastrophic loss of life,” said Julie Reed, a historian and Cherokee Nation citizen who teaches at Penn State University.

The push for a delegate after nearly two centuries also reflects the wider effort by Native Americans to exercise self-governance in ways that would have been unrecognizable to previous generations in Indian Country, a federal designation for land under tribal jurisdiction.

Native candidates have recently won congressional seats in states ranging from Alaska to Kansas. Some tribes are buying back ancestral lands. And Indigenous nations are expanding their own criminal justice systems across the country.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“The 1950s was the lowest point of Indian sovereignty,” said Robert J. Miller, a citizen of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma and a law professor at Arizona State University, citing the failed attempt by the U.S. government to disband tribes and relocate their members to cities. “The comeback has been incredible.”

Such breakthroughs, however, are taking place against the backdrop of other challenges, including those before the Supreme Court. In one ruling in June that upended longstanding precedents, the justices expanded the power of state governments over tribal nations.

The 5-4 ruling, which allows states to charge non-Indians for crimes committed against Indians on tribal land, stunned experts on Native American law and weakened a major decision from just two years before that had established the authority of tribal or federal courts on Indian land. (Tribal courts would retain authority over Native Americans who commit crimes on the reservation.)

Another case set to be heard by the court this year, challenging a 1978 law giving Native Americans preference in adopting Native children, could be just as unsettling. The law was intended to put an end to policies allowing Native children to be forcibly taken from their homes and placed by child welfare agencies in non-Native homes.

Plaintiffs, including the State of Texas, argue that the law created a system illegally based on race. But many tribal nations, including the Cherokees, have lined up against the challenge.

New measures at the state level are also flaring tempers, including an Oklahoma law banning schools from teaching material that could cause students discomfort or psychological stress because of their race.

Cherokees Ask U.S. to Make Good on a 187-Year-Old Promise, for a Start

The demand that Congress honor a treaty and seat a nonvoting delegate comes amid growing clashes over sovereignty and a tight race for Oklahoma’s governor, a Cherokee citizen.