There are people in Bedford-Stuyvesant who still talk about a pickup basketball game that took place in the neighborhood back in the summer of 1958 or ’59. The details of the story largely depend “on which griot is telling it,” as one old-timer recently put it, but if the best version is to be believed, the game featured one of the most spectacular collections of athletic talent ever assembled on a patch of blacktop.

The guys running up and down the court in Brooklyn that day supposedly included Bob Gibson, one of the greatest pitchers in the history of baseball; Jim Brown, arguably the greatest running back of all time; and the future basketball Hall of Famers Larry Brown, Lenny Wilkens and Oscar Robertson.

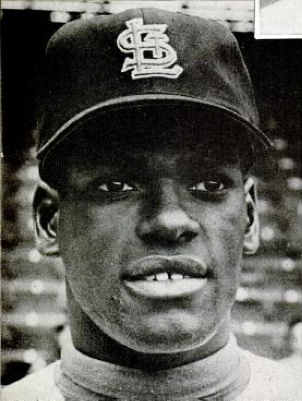

And a 16-year-old named Connie Hawkins.

Hawkins was a local high school player, maybe the best in the city. As the story goes, he went head-to-head with Robertson, who had just won a national scoring title at the University of Cincinnati. The college star was visiting friends in New York that summer. “I drove up there and stayed for two weeks,” he recently recalled. “I was just having fun.”

Robertson now says he didn’t play in Brooklyn, but the neighborhood’s oral historians insist otherwise. As they tell it, his appearance at St. Andrew’s Playground on Kingston Avenue — or Kingston Park, as most people called it — sent tremors of excitement through the streets. “Cars would come along, and people would stop at the light and say, ‘You’ll never believe what’s going on,’” Ed Towns, a former congressman from the district, remembered. Soon kids were scaling fences to catch a glimpse of the action. “Connie slowed Oscar’s game considerably,” said the former councilman Albert Vann, who claims he was there.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Of the six stars who are said to have played in that game, Hawkins, who died in 2017, may have actually had the highest ceiling. Lenny Wilkens, who grew up in Bed-Stuy and later spent 45 years in the N.B.A. as a player and as a coach, recalled Hawkins as an athlete with enormous potential. “He was one of those young men that you knew was destined to really be successful,” he recently said.

Larry Brown, another legendary player who was born in Brooklyn, once described him as “simply the greatest individual player” he had ever seen.

But in 1961, while he was in college, Hawkins was falsely accused of getting involved in a gambling scheme and was barred from playing in the N.B.A. He spent the prime of his career wearing out his knees in scrappier leagues, astonishing small crowds with feats of agility and creativity that were rarely captured on film.

To honor the street-ball legend, a group of guys from Bed-Stuy who grew up hearing tales of his underappreciated exploits have petitioned the city to rename the basketball courts at St. Andrew’s Playground after him. That may sound like an easy win. It’s hard to imagine how anyone could object to honoring a local hero whose due has been long denied.

And yet their effort has been met with resistance — not from the newcomers who are buying up the neighborhood, one $2 million brownstone at a time — but from another group of longtime residents who have just as much reverence for Brooklyn’s basketball history as they do. As the members of this rival faction see it, someone deserves to be on a plaque in that park, but it isn’t Connie Hawkins.

The expanse of cracked pavement that the Parks Department calls St. Andrew’s Playground spans a block on the southern edge of Bed-Stuy. Back in the 1950s, when the city was the undisputed capital of basketball, the park was considered “the capital of basketball in New York,” Ray Haskins, an esteemed coach and teacher from the neighborhood, recently contended. Today, weeds grow from the fissures that snake across the courts, and the softball field is riddled with holes. A newcomer would have no way of guessing that the place is a landmark.

More at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/18/nyregion/connie-hawkins-brooklyn-basketball-playground.html

The guys running up and down the court in Brooklyn that day supposedly included Bob Gibson, one of the greatest pitchers in the history of baseball; Jim Brown, arguably the greatest running back of all time; and the future basketball Hall of Famers Larry Brown, Lenny Wilkens and Oscar Robertson.

And a 16-year-old named Connie Hawkins.

Hawkins was a local high school player, maybe the best in the city. As the story goes, he went head-to-head with Robertson, who had just won a national scoring title at the University of Cincinnati. The college star was visiting friends in New York that summer. “I drove up there and stayed for two weeks,” he recently recalled. “I was just having fun.”

Robertson now says he didn’t play in Brooklyn, but the neighborhood’s oral historians insist otherwise. As they tell it, his appearance at St. Andrew’s Playground on Kingston Avenue — or Kingston Park, as most people called it — sent tremors of excitement through the streets. “Cars would come along, and people would stop at the light and say, ‘You’ll never believe what’s going on,’” Ed Towns, a former congressman from the district, remembered. Soon kids were scaling fences to catch a glimpse of the action. “Connie slowed Oscar’s game considerably,” said the former councilman Albert Vann, who claims he was there.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Of the six stars who are said to have played in that game, Hawkins, who died in 2017, may have actually had the highest ceiling. Lenny Wilkens, who grew up in Bed-Stuy and later spent 45 years in the N.B.A. as a player and as a coach, recalled Hawkins as an athlete with enormous potential. “He was one of those young men that you knew was destined to really be successful,” he recently said.

Larry Brown, another legendary player who was born in Brooklyn, once described him as “simply the greatest individual player” he had ever seen.

But in 1961, while he was in college, Hawkins was falsely accused of getting involved in a gambling scheme and was barred from playing in the N.B.A. He spent the prime of his career wearing out his knees in scrappier leagues, astonishing small crowds with feats of agility and creativity that were rarely captured on film.

To honor the street-ball legend, a group of guys from Bed-Stuy who grew up hearing tales of his underappreciated exploits have petitioned the city to rename the basketball courts at St. Andrew’s Playground after him. That may sound like an easy win. It’s hard to imagine how anyone could object to honoring a local hero whose due has been long denied.

And yet their effort has been met with resistance — not from the newcomers who are buying up the neighborhood, one $2 million brownstone at a time — but from another group of longtime residents who have just as much reverence for Brooklyn’s basketball history as they do. As the members of this rival faction see it, someone deserves to be on a plaque in that park, but it isn’t Connie Hawkins.

The expanse of cracked pavement that the Parks Department calls St. Andrew’s Playground spans a block on the southern edge of Bed-Stuy. Back in the 1950s, when the city was the undisputed capital of basketball, the park was considered “the capital of basketball in New York,” Ray Haskins, an esteemed coach and teacher from the neighborhood, recently contended. Today, weeds grow from the fissures that snake across the courts, and the softball field is riddled with holes. A newcomer would have no way of guessing that the place is a landmark.

More at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/18/nyregion/connie-hawkins-brooklyn-basketball-playground.html