The first sign of serious trouble for the drought-stricken American Southwest could be a whirlpool.

It could happen if the surface of Lake Powell, a man-made reservoir along the Colorado River that’s already a quarter of its former size, drops another 38 feet down the concrete face of the 710-foot Glen Canyon Dam here. At that point, the surface would be approaching the tops of eight underwater openings that allow river water to pass through the hydroelectric dam.

The normally placid Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, could suddenly transform into something resembling a funnel, with water circling the openings, the dam’s operators say.

If that happens, the massive turbines that generate electricity for 4.5 million people would have to shut down — after nearly 60 years of use — or risk destruction from air bubbles. The only outlet for Colorado River water from the dam would then be a set of smaller, deeper and rarely used bypass tubes with a far more limited ability to pass water downstream to the Grand Canyon and the cities and farms in Arizona, Nevada and California.

Such an outcome — known as a “minimum power pool” — was once unfathomable here. Now, the federal government projects that day could come as soon as July.

Worse, officials warn, is the possibility of an even more catastrophic event. That is if the water level falls all the way to the lowest holes, so only small amounts could pass through the dam. Such a scenario — called “dead pool” — would transform Glen Canyon Dam from something that regulates an artery of national importance into a hulking concrete plug corking the Colorado River.

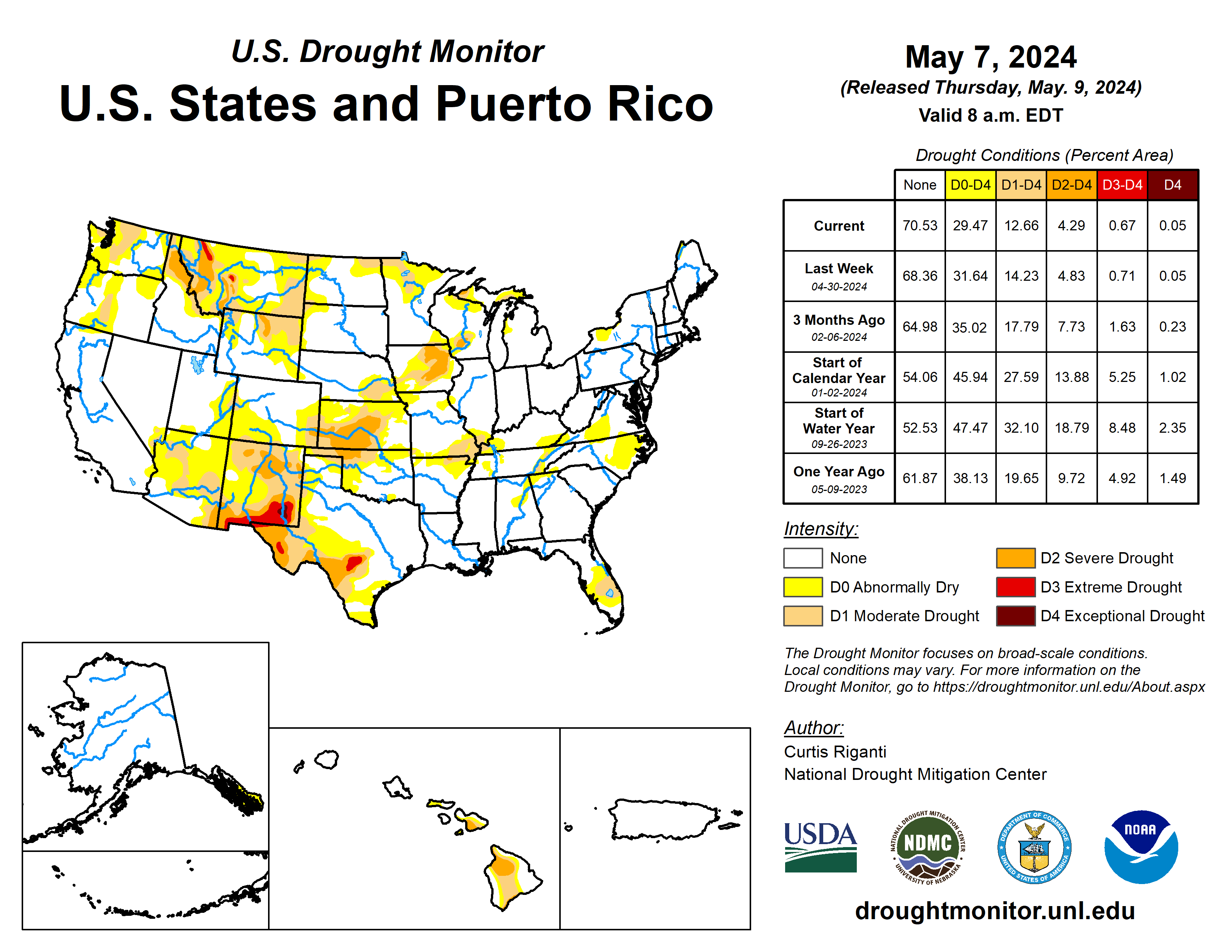

Anxiety about such outcomes has worsened this year as a long-running drought has intensified in the Southwest. Reservoirs and groundwater supplies across the region have fallen dramatically, and states and cities have faced restrictions on water use amid dwindling supplies. The Colorado River, which serves roughly 1 in 10 Americans, is the region’s most important waterway.

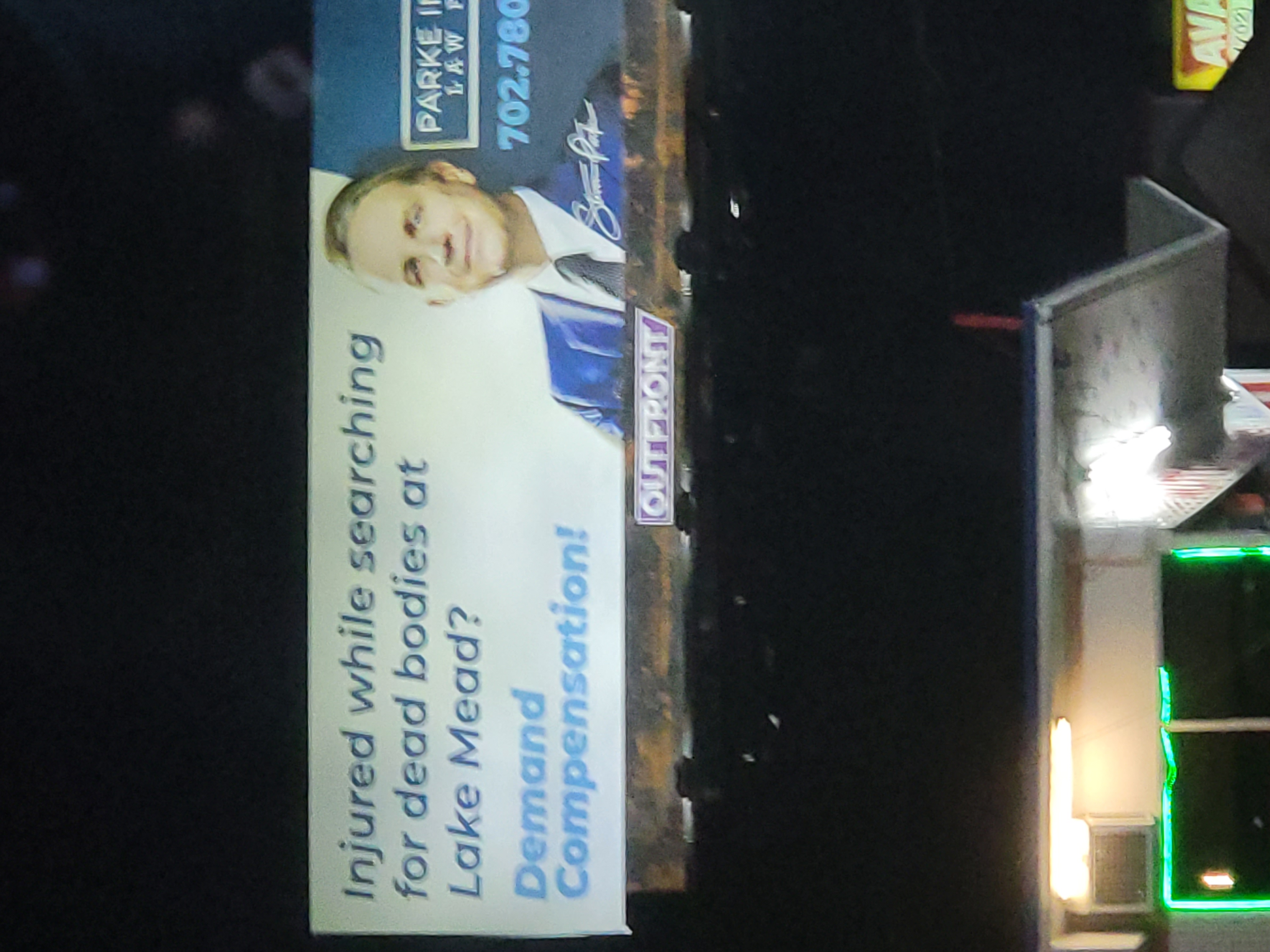

The 1,450-mile river starts in the Colorado Rockies and ends in the Sea of Cortez in Mexico. There are more than a dozen dams along the river, creating major reservoirs such as Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

A California condor spreads its wings as it rests on the Navajo Bridge above the Colorado River in Marble Canyon, Ariz. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

A parched area of Lake Powell near Lone Rock in Big Water. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Green algae and water stains are seen along a Colorado River canyon wall in Page, Ariz. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

On the way to such dire outcomes at Lake Powell — which federal officials have begun both planning for and working aggressively to avoid — scientists and dam operators say water temperatures in the Grand Canyon would hit a roller coaster, going frigid overnight and then heating up again, throwing the iconic ecosystem into turmoil. Lake Powell’s surface has already fallen 170 feet.

Lake Powell drought threatens power loss for millions

1:27

In October 2022, Lake Powell was a quarter full due to a historic drought, which threatened power supplied to millions by the Glen Canyon Dam in Page, Ariz. (Video: John Farrell/The Washington Post)

Lucrative industries that attract visitors from around the world — the rainbow trout fishery above Lees Ferry, rafting trips through the Grand Canyon — would be threatened. And eventually the only water escaping to the Colorado River basin’s southern states and Mexico could be what flows into Lake Powell from the north and sloshes over the lip of the dam’s lowest holes.

“A complete doomsday scenario,” said Bob Martin, deputy power manager at Glen Canyon Dam, as he peered down at the shimmering blue of Lake Powell from the rim of the dam.

The Colorado River is in crisis and it's getting worse every day

Water from Padre Bay in Utah flows between a mesa. Padre Bay connects with Lake Powell. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

“There was a time in my professional career that if anybody from Reclamation ever said that, they’d be fired on the spot,” said Schmidt, who served as the chief of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center during the Obama administration. Even raising that issue is “a huge sea change telling you how different the world is.”

This year, the Biden administration called on the seven states of the Colorado River basin to cut water consumption by 2 to 4 million acre-feet — up to a third of the river’s annual average flow — to protect power generation and avoid such dire outcomes. But negotiations have not produced an agreement. And the Interior Department has not yet mandated those cuts, despite missing its own August deadline to reach an agreement.

A boat moves around Horseshoe Bend along the Colorado River in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

People camp along Lake Powell in Big Water. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

People silhouetted along a Colorado River canyon wall in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Boats parked at the bottom of Horseshoe Bend along the Colorado River in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

But these types of ominous scenarios are starting to be considered. With Lake Powell at one-quarter full, Reclamation has begun a feasibility study on the prospect of harnessing the deeper bypass tubes for power generation. The entity that markets Glen Canyon’s electricity — the Western Area Power Administration, known as WAPA and part of the Energy Department — is working with two national laboratories to assess what electricity would be available for purchase if Glen Canyon shut down.

And construction is also underway on a project to install deeper pipes to protect the city of Page, Ariz., and its 7,000 residents, from losing its supply of drinking water.

The chances of hitting minimum power pool (lake elevation 3,490 feet above sea level) within the next two years is part of Reclamation’s minimum probable forecast, and more likely scenarios have water levels staying above that threshold. But researchers including Schmidt have documented how Reclamation’s projections have been too optimistic in recent years amid the warming climate and historic drought that is wringing water out of the West on a grand scale.

“The critical part about what’s been happening and what climate change is forcing us to do is: We have to look more at the extremes,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of Arizona’s Department of Water Resources, said in an interview. “We’ve got to plan for the low end.”

It could happen if the surface of Lake Powell, a man-made reservoir along the Colorado River that’s already a quarter of its former size, drops another 38 feet down the concrete face of the 710-foot Glen Canyon Dam here. At that point, the surface would be approaching the tops of eight underwater openings that allow river water to pass through the hydroelectric dam.

The normally placid Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, could suddenly transform into something resembling a funnel, with water circling the openings, the dam’s operators say.

If that happens, the massive turbines that generate electricity for 4.5 million people would have to shut down — after nearly 60 years of use — or risk destruction from air bubbles. The only outlet for Colorado River water from the dam would then be a set of smaller, deeper and rarely used bypass tubes with a far more limited ability to pass water downstream to the Grand Canyon and the cities and farms in Arizona, Nevada and California.

Such an outcome — known as a “minimum power pool” — was once unfathomable here. Now, the federal government projects that day could come as soon as July.

Worse, officials warn, is the possibility of an even more catastrophic event. That is if the water level falls all the way to the lowest holes, so only small amounts could pass through the dam. Such a scenario — called “dead pool” — would transform Glen Canyon Dam from something that regulates an artery of national importance into a hulking concrete plug corking the Colorado River.

Anxiety about such outcomes has worsened this year as a long-running drought has intensified in the Southwest. Reservoirs and groundwater supplies across the region have fallen dramatically, and states and cities have faced restrictions on water use amid dwindling supplies. The Colorado River, which serves roughly 1 in 10 Americans, is the region’s most important waterway.

The 1,450-mile river starts in the Colorado Rockies and ends in the Sea of Cortez in Mexico. There are more than a dozen dams along the river, creating major reservoirs such as Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

A California condor spreads its wings as it rests on the Navajo Bridge above the Colorado River in Marble Canyon, Ariz. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

A parched area of Lake Powell near Lone Rock in Big Water. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Green algae and water stains are seen along a Colorado River canyon wall in Page, Ariz. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

On the way to such dire outcomes at Lake Powell — which federal officials have begun both planning for and working aggressively to avoid — scientists and dam operators say water temperatures in the Grand Canyon would hit a roller coaster, going frigid overnight and then heating up again, throwing the iconic ecosystem into turmoil. Lake Powell’s surface has already fallen 170 feet.

Lake Powell drought threatens power loss for millions

1:27

In October 2022, Lake Powell was a quarter full due to a historic drought, which threatened power supplied to millions by the Glen Canyon Dam in Page, Ariz. (Video: John Farrell/The Washington Post)

Lucrative industries that attract visitors from around the world — the rainbow trout fishery above Lees Ferry, rafting trips through the Grand Canyon — would be threatened. And eventually the only water escaping to the Colorado River basin’s southern states and Mexico could be what flows into Lake Powell from the north and sloshes over the lip of the dam’s lowest holes.

“A complete doomsday scenario,” said Bob Martin, deputy power manager at Glen Canyon Dam, as he peered down at the shimmering blue of Lake Powell from the rim of the dam.

The Colorado River is in crisis and it's getting worse every day

Water from Padre Bay in Utah flows between a mesa. Padre Bay connects with Lake Powell. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

‘A catastrophe for the entire system’

In August, the Bureau of Reclamation announced it would support studies to find out if physical modifications could be made to Glen Canyon Dam to allow water to be released below critical elevations, including dead pool. That implies studying such costly and time-consuming construction projects as drilling tunnels through the Navajo sandstone at river level, said Jack Schmidt, a Colorado River expert at Utah State University.“There was a time in my professional career that if anybody from Reclamation ever said that, they’d be fired on the spot,” said Schmidt, who served as the chief of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center during the Obama administration. Even raising that issue is “a huge sea change telling you how different the world is.”

This year, the Biden administration called on the seven states of the Colorado River basin to cut water consumption by 2 to 4 million acre-feet — up to a third of the river’s annual average flow — to protect power generation and avoid such dire outcomes. But negotiations have not produced an agreement. And the Interior Department has not yet mandated those cuts, despite missing its own August deadline to reach an agreement.

A boat moves around Horseshoe Bend along the Colorado River in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

People camp along Lake Powell in Big Water. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

People silhouetted along a Colorado River canyon wall in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Boats parked at the bottom of Horseshoe Bend along the Colorado River in Page. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

But these types of ominous scenarios are starting to be considered. With Lake Powell at one-quarter full, Reclamation has begun a feasibility study on the prospect of harnessing the deeper bypass tubes for power generation. The entity that markets Glen Canyon’s electricity — the Western Area Power Administration, known as WAPA and part of the Energy Department — is working with two national laboratories to assess what electricity would be available for purchase if Glen Canyon shut down.

And construction is also underway on a project to install deeper pipes to protect the city of Page, Ariz., and its 7,000 residents, from losing its supply of drinking water.

The chances of hitting minimum power pool (lake elevation 3,490 feet above sea level) within the next two years is part of Reclamation’s minimum probable forecast, and more likely scenarios have water levels staying above that threshold. But researchers including Schmidt have documented how Reclamation’s projections have been too optimistic in recent years amid the warming climate and historic drought that is wringing water out of the West on a grand scale.

“The critical part about what’s been happening and what climate change is forcing us to do is: We have to look more at the extremes,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of Arizona’s Department of Water Resources, said in an interview. “We’ve got to plan for the low end.”