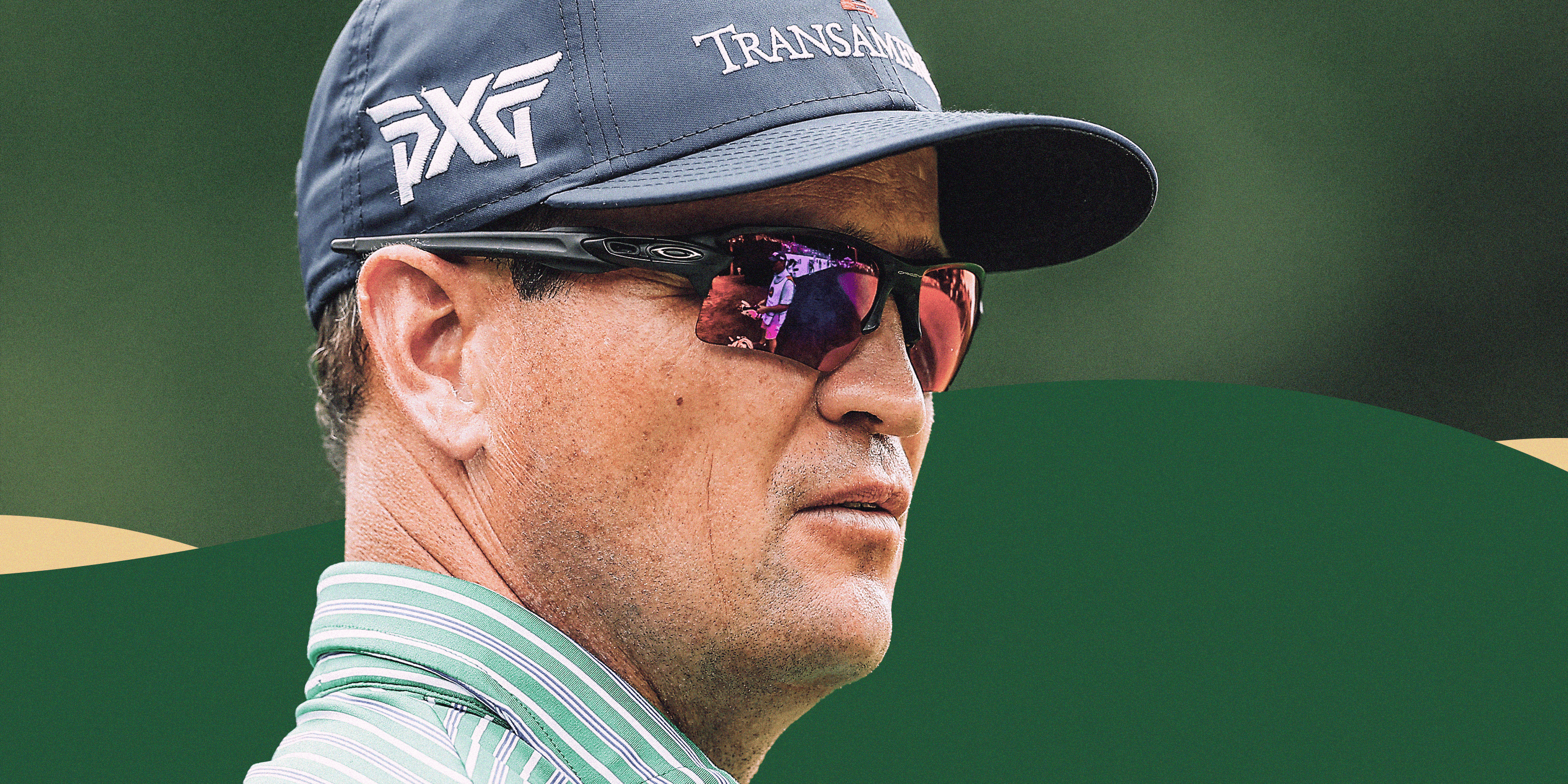

Rethinking Zach Johnson, the unlikeliest Ryder Cup captain

It’s been 31 years since a U.S. team won the Ryder Cup on European soil. Can an overlooked champion break the streak?

If you think about it, Zach Johnson’s two pinnacle career moments were, at the time, eclipsed by what didn’t happen.

April 2007. The man survived the most brutal of Masters Tournaments. Cool, then cold, then furiously windy. Augusta was a mess of vests and mock turtlenecks. Johnson played in Sunday’s third-to-last pairing, completed a dramatic up-and-down on 18, then buried his face into his wife Kim’s shoulder, trying to stifle his emotions. He was the tournament’s solo leader. Fairy tale stuff. All our focus, though, was on Tiger Woods, who’d held the lead early in the fourth round, lost it, stormed back with an eagle on 13, and was two back with two to go. But Tiger’s surge fizzled and to this day you can still hear the air coming out of the broadcast’s balloon. Johnson, a little-known Iowan, won the Masters with a final score of 289 (+1), tying for the highest winning score ever at Augusta. Presenting the Top 10 list on “Letterman” days later, he came to No. 6: “Even I’ve never heard of me.” The next day, Tiger was on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

And July 2015. The Open Championship at St. Andrews. Another brutal week. Enough wind and rain to force only the second Monday finish in a tournament dating to the Druids. Johnson shot a low final-round 66, then sat in the clubhouse for roughly an hour as the world watched Jordan Spieth. Golf’s wunderkind was eyeing the third leg of a calendar year Grand Slam, falling from heaven as some kind of marketable manifestation of a post-Tiger world. He was supposed to win. But he finished one shot back. Johnson returned to the course to beat Louis Oosthuizen and Marc Leishman in a four-hole playoff. The next day’s New York Times headline read: “Zach Johnson’s Grand Win Slams Door on Jordan Spieth’s Bid for History.”

This is how Zach Johnson has existed in golf’s collective consciousness for much of his career: always there, easily overlooked, oddly successful. Davis Love III, one of Johnson’s closest friends, is bemused. “Zach gets introduced on the first tee at a tournament and you kinda go, ‘Oh, wow, dang — he won two majors and (12) tournaments?’”

But now everything is different. Johnson is in Rome this week as United States captain for the 2023 Ryder Cup — what feels like an epochal moment for one of the game’s oft-ignored figures. He’s here, in part, as a product of duress. Early in 2022, around the outset of professional golf’s turf war between the PGA Tour and LIV Golf, a group of Johnson’s peers — Love III and other U.S. Ryder Cup leaders — urged him to accept the captaincy. As Love puts it, Johnson was seen as “someone who everyone trusts.”

Johnson didn’t see any of this coming.

“Given (the candidates) ahead of me in age and, I would say, clout, I thought there were a couple of other guys that would probably be chosen,” Johnson says. “To be honest, I thought I might be in line for a Presidents Cup a few years down the road, potentially, but not this.”

Johnson is speaking by phone, walking his dogs, Augie (Augusta) and Andy (St. Andrews), around his neighborhood in St. Simons Island. It’s one week until departure for the Ryder Cup and he’s attempting to process all of this. He’s walking fast enough to breathe hard. St. Simons is a resort community along the southern Georgia coast, where Johnson’s family resides, about a thousand miles from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the hometown with which he deeply identifies.

It’s been 31 years since a U.S. team won the Ryder Cup on European soil, when Tom Watson captained the Americans to a win at The Belfry. The streak rankles those associated with it. Often, the Americans have gone abroad with more top-to-bottom talent and higher rankings, etc., etc., only to return humbled.

A win this week? Massaging a lineup that finally cracks the code? Spraying champagne at Marco Simone Golf Club? It’s a recipe to possibly change how Johnson is viewed at large. Maybe this is what it will take for some to appreciate how he got here.

“I don’t know,” Johnson says, “but I’ve always been someone who’s very efficient in capitalizing on opportunities.”

As Jamie Bermel remembers it, 17-year-old Zach Johnson shot 80-81 in the Iowa state tournament as a Cedar Rapids Regis High senior.

Like most Midwest kids, Johnson grew up stashing his clubs in a garage for six months a year, when Iowa turned cold and Hawkeyes football took hold. Young Zach was an athlete. Soccer, baseball, whatever. He liked team sports and threw his body around. Good thing his dad was a chiropractor.

Golf was always a means to an end. Johnson began playing around 10, finding instruction at Elmcrest Country Club in Cedar Rapids. He ended up being good enough to earn all-county honors, but he was mostly off the radar of college coaches. Bermel, today the coach at Kansas University, then the coach at Drake University in Des Moines, only noticed him by chance. He was recruiting another young man who stood over the ball too long and got so fed up watching him that he began checking out his 5-foot-8 playing partner. The kid had a nice shape to his shot.

The bigger schools? They knew nothing of the young man who would go on to be the greatest player Iowa would ever produce. Why? “Because he wasn’t all that good,” Bermel says.

Instead, Johnson chose between interest from Drake and St. Ambrose University, an NAIA school in Davenport.

This, in reality, should’ve been it. Johnson was never Missouri Valley Conference player of the year. He was never even an all-conference selection. He wasn’t the best player on his team. Most players of his caliber would have gone to Drake, played four years of college golf and then gone into teaching or business or something.

Instead, after graduation, Zach Johnson declared himself a professional.

Years later, Morris Pickens, Johnson’s sports psychologist, would explain: “Zach always had the mindset that he would keep getting better, and at some point, his good would be better than other guys’ good. He’s operated with the idea that, if it’s a race of endurance, and his process being better than their process, then he’ll take his chance.”

But at the time, people thought Zach was delusional.

“I thought, ‘holy sh–, you’re the third guy at Drake and you’re gonna turn pro?’” Bermel said. “There are a lot of guys every year who think they can make it. Usually, they figure out how it’s gonna end.”