Fred “Duke” Slater was a University of Iowa football great who became the first Black lineman in the NFL and then a respected lawyer and judge in Chicago.

Slater was a star tackle for the Hawks from 1918 through 1921. The 6-foot, 1-inch Slater was named an All-American tackle in 1921 and was called the “Rock of Gibraltar” on the field.

But few stories about Slater tell of an early, humbling experience that the all-star athlete experienced at Iowa, a mistake that was rectified and perhaps turned him into the man remembered today for his character and humility.

Slater, the son of a Black pastor, played pickup football as a kid on the South Side of Chicago. When he was 13, his family moved to Clinton, Iowa, where he played football for three years, leading his high school team to two state championships before graduating in 1916.

Slater played without a helmet at Clinton and during at least part of his college career. His family had little money, and Slater had to choose between buying shoes or a helmet. Slater, who had really big feet that were hard to fit, chose shoes.

After high school, Slater had intended to go to Lenox College in Hopkinton and then to Harvard University.

“But a group of Iowa alumni headed by Judge (Ralph P.) Howell persuaded me to go to Iowa,” Slater told a reporter in Iowa City in 1952. “I’m glad they did. I’ve spent many a happy day in this town.”

Slater came to Iowa in September 1917 with a four-year scholarship.

In a scrimmage against the varsity team, the new plays the coach had designed worked great — on the left side of the field — but not on the right side where Slater “smeared two-thirds of the attempts made by the varsity to gain through that point,” The Gazette reported.

A few days after that story hit print, though, Slater was cut from the team and expelled after confessing he had taken a watch from another player’s belongings at the gym. He was told no charges would be filed if he left Iowa City immediately.

Fences were mended, though, and Slater returned to Iowa, where he was invited to a postseason Iowa football banquet in November. He and a member of the athletic faculty provided the entertainment — a boxing match — that proved so engrossing the players forgot to elect a team captain for the next year.

In 1921, Slater’s All-American year, Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne said Slater was the greatest tackle he had ever seen play. That was after Iowa’s 10-7 upset victory over the Irish, which clinched the mythical national title for Iowa.

Slater also lettered in track and field at Iowa three years.

Academically, Slater switched from a liberal-arts major to prelaw when he was a junior. In March 1922, he was chosen to present at the fifth annual Law Jubilee put on by the Iowa Law School Students’ Association. Among the other presenters was future Iowa Gov. Bourke B. Hickenlooper.

Slater began playing professional football with the Rock Island Independents in 1922, where he was the first Black lineman in the NFL. In his first game, he swatted down a pass from the Green Bay Packers quarterback Curly Lambeau on Green Bay’s final drive of the game.

He joined the Chicago Cardinals in 1926 — the same year he married fellow UI graduate Etta Searcy — and continued as a star player, being named to All-Pro teams seven times, a record for an NFL lineman. He retired after the 1931 season.

While Slater was playing professional football, he returned to the UI in the offseason to take classes at the College of Law, graduating in 1928.

After leaving football, Slater began practicing law in Chicago, where he worked as an assistant district attorney.

In 1948, he was elected a judge in the Chicago municipal court. In 1960, he was the first Black named to the Cook County Superior Court, the highest court in Chicago at the time. He then became a Cook County Circuit Court judge.

Through the years, Slater remained an Iowa booster, steering young Black athletes to Iowa City. When the NFL unofficially banned Black players from 1934 to 1945, Slater organized competitions for young Black players.

Slater was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951. He was named to the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Centennial Class of 2020.

Frederick “Duke” Slater had been a judge for almost 20 years when he died in 1966, at age 67, of stomach cancer.

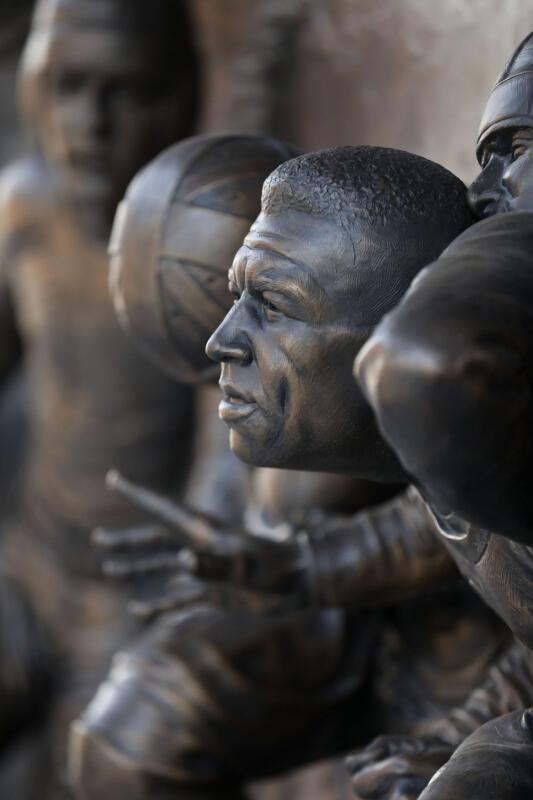

In 2021, the University of Iowa announced the field at Kinnick Stadium would be named the Duke Slater Field in his honor.

www.thegazette.com

www.thegazette.com

Slater was a star tackle for the Hawks from 1918 through 1921. The 6-foot, 1-inch Slater was named an All-American tackle in 1921 and was called the “Rock of Gibraltar” on the field.

But few stories about Slater tell of an early, humbling experience that the all-star athlete experienced at Iowa, a mistake that was rectified and perhaps turned him into the man remembered today for his character and humility.

In Clinton

Slater, the son of a Black pastor, played pickup football as a kid on the South Side of Chicago. When he was 13, his family moved to Clinton, Iowa, where he played football for three years, leading his high school team to two state championships before graduating in 1916.

Slater played without a helmet at Clinton and during at least part of his college career. His family had little money, and Slater had to choose between buying shoes or a helmet. Slater, who had really big feet that were hard to fit, chose shoes.

To Iowa City

After high school, Slater had intended to go to Lenox College in Hopkinton and then to Harvard University.

“But a group of Iowa alumni headed by Judge (Ralph P.) Howell persuaded me to go to Iowa,” Slater told a reporter in Iowa City in 1952. “I’m glad they did. I’ve spent many a happy day in this town.”

Slater came to Iowa in September 1917 with a four-year scholarship.

In a scrimmage against the varsity team, the new plays the coach had designed worked great — on the left side of the field — but not on the right side where Slater “smeared two-thirds of the attempts made by the varsity to gain through that point,” The Gazette reported.

A few days after that story hit print, though, Slater was cut from the team and expelled after confessing he had taken a watch from another player’s belongings at the gym. He was told no charges would be filed if he left Iowa City immediately.

Fences were mended, though, and Slater returned to Iowa, where he was invited to a postseason Iowa football banquet in November. He and a member of the athletic faculty provided the entertainment — a boxing match — that proved so engrossing the players forgot to elect a team captain for the next year.

In 1921, Slater’s All-American year, Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne said Slater was the greatest tackle he had ever seen play. That was after Iowa’s 10-7 upset victory over the Irish, which clinched the mythical national title for Iowa.

Slater also lettered in track and field at Iowa three years.

Academically, Slater switched from a liberal-arts major to prelaw when he was a junior. In March 1922, he was chosen to present at the fifth annual Law Jubilee put on by the Iowa Law School Students’ Association. Among the other presenters was future Iowa Gov. Bourke B. Hickenlooper.

Pro football

Slater began playing professional football with the Rock Island Independents in 1922, where he was the first Black lineman in the NFL. In his first game, he swatted down a pass from the Green Bay Packers quarterback Curly Lambeau on Green Bay’s final drive of the game.

He joined the Chicago Cardinals in 1926 — the same year he married fellow UI graduate Etta Searcy — and continued as a star player, being named to All-Pro teams seven times, a record for an NFL lineman. He retired after the 1931 season.

Law career

While Slater was playing professional football, he returned to the UI in the offseason to take classes at the College of Law, graduating in 1928.

After leaving football, Slater began practicing law in Chicago, where he worked as an assistant district attorney.

In 1948, he was elected a judge in the Chicago municipal court. In 1960, he was the first Black named to the Cook County Superior Court, the highest court in Chicago at the time. He then became a Cook County Circuit Court judge.

Through the years, Slater remained an Iowa booster, steering young Black athletes to Iowa City. When the NFL unofficially banned Black players from 1934 to 1945, Slater organized competitions for young Black players.

Honors

Slater was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951. He was named to the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Centennial Class of 2020.

Frederick “Duke” Slater had been a judge for almost 20 years when he died in 1966, at age 67, of stomach cancer.

In 2021, the University of Iowa announced the field at Kinnick Stadium would be named the Duke Slater Field in his honor.

The inimitable Fred ‘Duke’ Slater

Iowa football star was first Black lineman in the NFL before becoming a lawyer and judge in Chicago.