When Major League Baseball returned to Washington in 2005, the Nationals played their games at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. It had been 34 years since the city had a baseball team, but the stadium still held remnants of its last star before the game went away.

Deep in the upper deck, several seats were painted white, marking the longest home runs hit by Frank Howard, who during his seven seasons with the woeful Washington Senators was recognized as one of baseball’s strongest and most feared hitters.

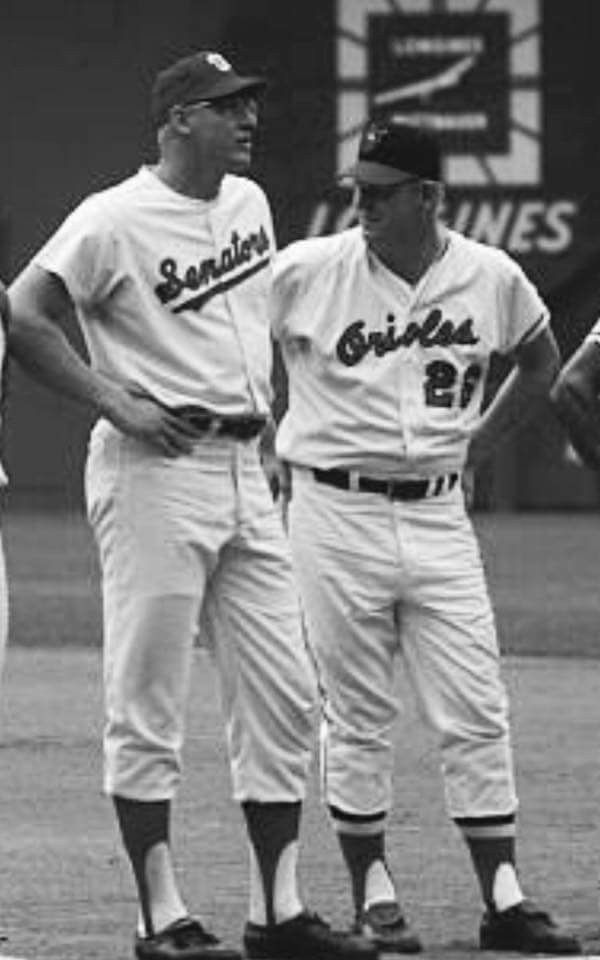

At 6-foot-7 and about 270 pounds, he was a towering force on an otherwise forgettable team, launching monumental home runs that sometimes flew more than 500 feet.

When the Nationals arrived in RFK Stadium more than three decades after Mr. Howard’s final game, players looked at the distant white seats in the upper deck and could not believe a baseball could be hit that far.

“They’d ask me, ‘Where was home plate back then?’” Washington Post sports columnist Thomas Boswell wrote in a 2016 online chat. “I’d say, ‘Right where it is now, give or take a foot or two.’ Not one player ever believed me. They considered it impossible.”

Mr. Howard, who twice led the American League in home runs and remained an enduring favorite of Washington’s disenfranchised baseball fans, died Oct. 30 at a hospital in Aldie, Va. He was 87.

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his daughter Catherine Braun.

A college basketball star at Ohio State, the Bunyanesque Mr. Howard chose a career in baseball instead, signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers. At a time when many players were relatively slight — San Francisco Giants superstar Willie Mays was about 5-foot-11 and 180 pounds — the bespectacled Mr. Howard stood out on the baseball diamond like a redwood.

In one of Mr. Howard’s first games with the Dodgers, he hit a foul ball that knocked out a teammate, Duke Snider, who was leading off third base. Mr. Howard was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1960, then seemed to fulfill his promise two years later, when he belted 31 home runs, with 119 runs batted in and a .296 batting average.

In 1963, when he helped lead the Dodgers to a four-game sweep over the New York Yankees in the World Series, he hit what was called “the longest double in the 41-year history of Yankee Stadium” off Hall of Fame pitcher Whitey Ford.

Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek recalled the moment to the Miami Herald in 1991: “Howard hit a line drive right over my head. I jumped for it and missed it by about a foot, maybe two, tops. There was a speaker in left center, 457 feet away. The ball hit the speaker and bounced back like a bullet … I don’t think it was higher than 10-12 feet all the way out.”

In the fourth and decisive game of the series, Mr. Howard launched a 450-foot home run off Ford to propel the Dodgers to a 2-1 victory.

“He was the only batter,” Ford later said, “who ever scared me.”

After slumping in 1964, Mr. Howard was contemplating retirement at age 28. An executive with a cardboard-box manufacturing company in Green Bay, Wis., where Mr. Howard had an offseason job, urged him to give baseball another chance.

“I think I am a realistic guy,” Mr. Howard told Sports Illustrated at the time. “I have the God-given talents of strength and leverage. I realize that I can never be a great ballplayer because a great ballplayer must be able to do five things well: run, field, throw, hit and hit with power. I am mediocre in four of those — but I can hit with power.”

Before the 1965 season, he was traded to Washington and regained his form, winning the American League’s Comeback Player of the Year award. In seven years with the Senators, he built a reputation as one of baseball’s leading sluggers and as one of the city’s most beloved athletes in any sport.

In May 1968, during his third season in Washington, Mr. Howard had a hot streak that has never been matched in baseball history. Over a six-game period, he slammed 10 home runs and drove in 17 runs. One home run in Detroit “bounced atop the 90-foot-high roof covering the upper deck and left the ballpark,” wrote Post reporter George Minot Jr., who estimated that the hit went at least 550 feet.

During his streak, Mr. Howard told the Hartford Courant in 2001, “I was thinking, somebody’s going to flip me” — throw at him — “pretty soon, because it’s part of our business. I thought someone was going to put a part in my hair, but they didn’t, so I figured I’ll settle in and keep cool. It was a fun week. Man alive, you’d like to crank like that for a couple of months.”

As his legend grew, Mr. Howard acquired a host of imposing nicknames, from Hondo to the Washington Monument to, perhaps most evocatively, the Capital Punisher. Several pitchers and infielders recounted how they leaped to catch hard-hit line drives off Mr. Howard’s bat — only to watch as they kept rising all the way into the outfield seats.

Around the American League, attendance rose whenever Mr. Howard and the otherwise hapless Senators came to town, as fans flocked to see how far he might hit the ball.

“No player can electrify a ballpark as much, simply by taking his bat to the plate and taking up a stance that tells the pitcher he is ready,” Post sports columnist Shirley Povich wrote.

In 1968, known as the “Year of the Pitcher,” Mr. Howard had 44 homers — eight more than any other player in the game. Before the next season, he demanded a three-year contract for $300,000 and refused to report for spring training.

He finally settled with the Senators’ new owner, Robert Short, on a one-year contract for more than $90,000, three weeks before the beginning of the season. When Ted Williams was named Senators manager in 1969, Mr. Howard changed his uniform number to 33 to allow Williams to wear the No. 9 jersey he had made famous during his Hall of Fame career with the Boston Red Sox.

Under Williams’s tutelage, Mr. Howard became a more complete hitter, drawing more walks than before, including a league-leading 132 in 1970. Williams was impressed by Mr. Howard’s work ethic and sheer strength.

“That son-of-a-gun is the biggest and strongest hitter who ever played this game, and that includes Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg — all of them,” Williams, said in 1969. “Nobody ever hit the ball harder and further, nobody.”

Mr. Howard hit a career-high 48 home runs in 1969, then led the league the next year with 44 homers and 126 RBIs. But as the Senators continued to lose, Short announced in late 1971 that he would move the franchise to Arlington, Tex.

As the jilted fans grew more surly, hanging Short in effigy and unfurling vulgar banners at the ballpark, Mr. Howard and teammates played their final games in Washington. “I hate to leave,” he told The Post. “We had a bunch of ragamuffins here in Washington in the seven years I played, but I’ve got to say that all of us always gave our best. We had a team spirit that was hard to beat.”

On Sept. 30, 1971, the Senators played their final game. They were leading the Yankees in the ninth inning, 7-5, when unruly fans stormed the field and began to pick up the bases and pieces of turf. The game was forfeited to the Yankees.

In the sixth inning of the game, Mr. Howard slugged a home run — the last ever hit by a Senator.

“That’s what the fans had come to see,” Minot wrote in The Post. “They rolled cheer after cheer upon his broad shoulders. He waved his batting helmet to them before disappearing into the dugout. Then he came out and tossed his cap into the crowd. And he came out again to blow kisses.”

“This is utopia,” Mr. Howard said after the game. “This is the greatest thrill of my life. What would top it?”

Deep in the upper deck, several seats were painted white, marking the longest home runs hit by Frank Howard, who during his seven seasons with the woeful Washington Senators was recognized as one of baseball’s strongest and most feared hitters.

At 6-foot-7 and about 270 pounds, he was a towering force on an otherwise forgettable team, launching monumental home runs that sometimes flew more than 500 feet.

When the Nationals arrived in RFK Stadium more than three decades after Mr. Howard’s final game, players looked at the distant white seats in the upper deck and could not believe a baseball could be hit that far.

“They’d ask me, ‘Where was home plate back then?’” Washington Post sports columnist Thomas Boswell wrote in a 2016 online chat. “I’d say, ‘Right where it is now, give or take a foot or two.’ Not one player ever believed me. They considered it impossible.”

Mr. Howard, who twice led the American League in home runs and remained an enduring favorite of Washington’s disenfranchised baseball fans, died Oct. 30 at a hospital in Aldie, Va. He was 87.

The cause was complications from a stroke, said his daughter Catherine Braun.

A college basketball star at Ohio State, the Bunyanesque Mr. Howard chose a career in baseball instead, signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers. At a time when many players were relatively slight — San Francisco Giants superstar Willie Mays was about 5-foot-11 and 180 pounds — the bespectacled Mr. Howard stood out on the baseball diamond like a redwood.

In one of Mr. Howard’s first games with the Dodgers, he hit a foul ball that knocked out a teammate, Duke Snider, who was leading off third base. Mr. Howard was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1960, then seemed to fulfill his promise two years later, when he belted 31 home runs, with 119 runs batted in and a .296 batting average.

In 1963, when he helped lead the Dodgers to a four-game sweep over the New York Yankees in the World Series, he hit what was called “the longest double in the 41-year history of Yankee Stadium” off Hall of Fame pitcher Whitey Ford.

Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek recalled the moment to the Miami Herald in 1991: “Howard hit a line drive right over my head. I jumped for it and missed it by about a foot, maybe two, tops. There was a speaker in left center, 457 feet away. The ball hit the speaker and bounced back like a bullet … I don’t think it was higher than 10-12 feet all the way out.”

In the fourth and decisive game of the series, Mr. Howard launched a 450-foot home run off Ford to propel the Dodgers to a 2-1 victory.

“He was the only batter,” Ford later said, “who ever scared me.”

After slumping in 1964, Mr. Howard was contemplating retirement at age 28. An executive with a cardboard-box manufacturing company in Green Bay, Wis., where Mr. Howard had an offseason job, urged him to give baseball another chance.

“I think I am a realistic guy,” Mr. Howard told Sports Illustrated at the time. “I have the God-given talents of strength and leverage. I realize that I can never be a great ballplayer because a great ballplayer must be able to do five things well: run, field, throw, hit and hit with power. I am mediocre in four of those — but I can hit with power.”

Before the 1965 season, he was traded to Washington and regained his form, winning the American League’s Comeback Player of the Year award. In seven years with the Senators, he built a reputation as one of baseball’s leading sluggers and as one of the city’s most beloved athletes in any sport.

In May 1968, during his third season in Washington, Mr. Howard had a hot streak that has never been matched in baseball history. Over a six-game period, he slammed 10 home runs and drove in 17 runs. One home run in Detroit “bounced atop the 90-foot-high roof covering the upper deck and left the ballpark,” wrote Post reporter George Minot Jr., who estimated that the hit went at least 550 feet.

During his streak, Mr. Howard told the Hartford Courant in 2001, “I was thinking, somebody’s going to flip me” — throw at him — “pretty soon, because it’s part of our business. I thought someone was going to put a part in my hair, but they didn’t, so I figured I’ll settle in and keep cool. It was a fun week. Man alive, you’d like to crank like that for a couple of months.”

As his legend grew, Mr. Howard acquired a host of imposing nicknames, from Hondo to the Washington Monument to, perhaps most evocatively, the Capital Punisher. Several pitchers and infielders recounted how they leaped to catch hard-hit line drives off Mr. Howard’s bat — only to watch as they kept rising all the way into the outfield seats.

Around the American League, attendance rose whenever Mr. Howard and the otherwise hapless Senators came to town, as fans flocked to see how far he might hit the ball.

“No player can electrify a ballpark as much, simply by taking his bat to the plate and taking up a stance that tells the pitcher he is ready,” Post sports columnist Shirley Povich wrote.

In 1968, known as the “Year of the Pitcher,” Mr. Howard had 44 homers — eight more than any other player in the game. Before the next season, he demanded a three-year contract for $300,000 and refused to report for spring training.

He finally settled with the Senators’ new owner, Robert Short, on a one-year contract for more than $90,000, three weeks before the beginning of the season. When Ted Williams was named Senators manager in 1969, Mr. Howard changed his uniform number to 33 to allow Williams to wear the No. 9 jersey he had made famous during his Hall of Fame career with the Boston Red Sox.

Under Williams’s tutelage, Mr. Howard became a more complete hitter, drawing more walks than before, including a league-leading 132 in 1970. Williams was impressed by Mr. Howard’s work ethic and sheer strength.

“That son-of-a-gun is the biggest and strongest hitter who ever played this game, and that includes Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg — all of them,” Williams, said in 1969. “Nobody ever hit the ball harder and further, nobody.”

Mr. Howard hit a career-high 48 home runs in 1969, then led the league the next year with 44 homers and 126 RBIs. But as the Senators continued to lose, Short announced in late 1971 that he would move the franchise to Arlington, Tex.

As the jilted fans grew more surly, hanging Short in effigy and unfurling vulgar banners at the ballpark, Mr. Howard and teammates played their final games in Washington. “I hate to leave,” he told The Post. “We had a bunch of ragamuffins here in Washington in the seven years I played, but I’ve got to say that all of us always gave our best. We had a team spirit that was hard to beat.”

On Sept. 30, 1971, the Senators played their final game. They were leading the Yankees in the ninth inning, 7-5, when unruly fans stormed the field and began to pick up the bases and pieces of turf. The game was forfeited to the Yankees.

In the sixth inning of the game, Mr. Howard slugged a home run — the last ever hit by a Senator.

“That’s what the fans had come to see,” Minot wrote in The Post. “They rolled cheer after cheer upon his broad shoulders. He waved his batting helmet to them before disappearing into the dugout. Then he came out and tossed his cap into the crowd. And he came out again to blow kisses.”

“This is utopia,” Mr. Howard said after the game. “This is the greatest thrill of my life. What would top it?”