THE GUNSHOT-DETECTION SYSTEM ShotSpotter has for years drawn criticism from activists and academics who believe the company behind the system, SoundThinking, places its microphone sensors primarily in low-income communities of color. Now, a WIRED analysis of data leaked from the company reveals the secret locations of ShotSpotter sensors around the globe and the US communities most directly impacted by the surveillance.

Until now, the exact locations of SoundThinking’s sensors have been kept secret from both its police department clients and the public at large. A leaked document, which WIRED obtained from a source under the condition of anonymity, details the alleged precise locations and uptime of 25,580 ShotSpotter microphones. The data exposes for the first time the reach of SoundThinking’s network of surveillance devices and adds new context to an ongoing debate between activists and academics who claim ShotSpotter perpetuates biased policing practices and proponents of the technology.

According to the document, SoundThinking equipment has been installed at more than a thousand elementary and high schools; they are perched atop dozens of billboards, scores of hospitals, and within more than a hundred public housing complexes. They can be found on significant US government buildings, including the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Justice, and the US Court of Appeals in Washington, DC.

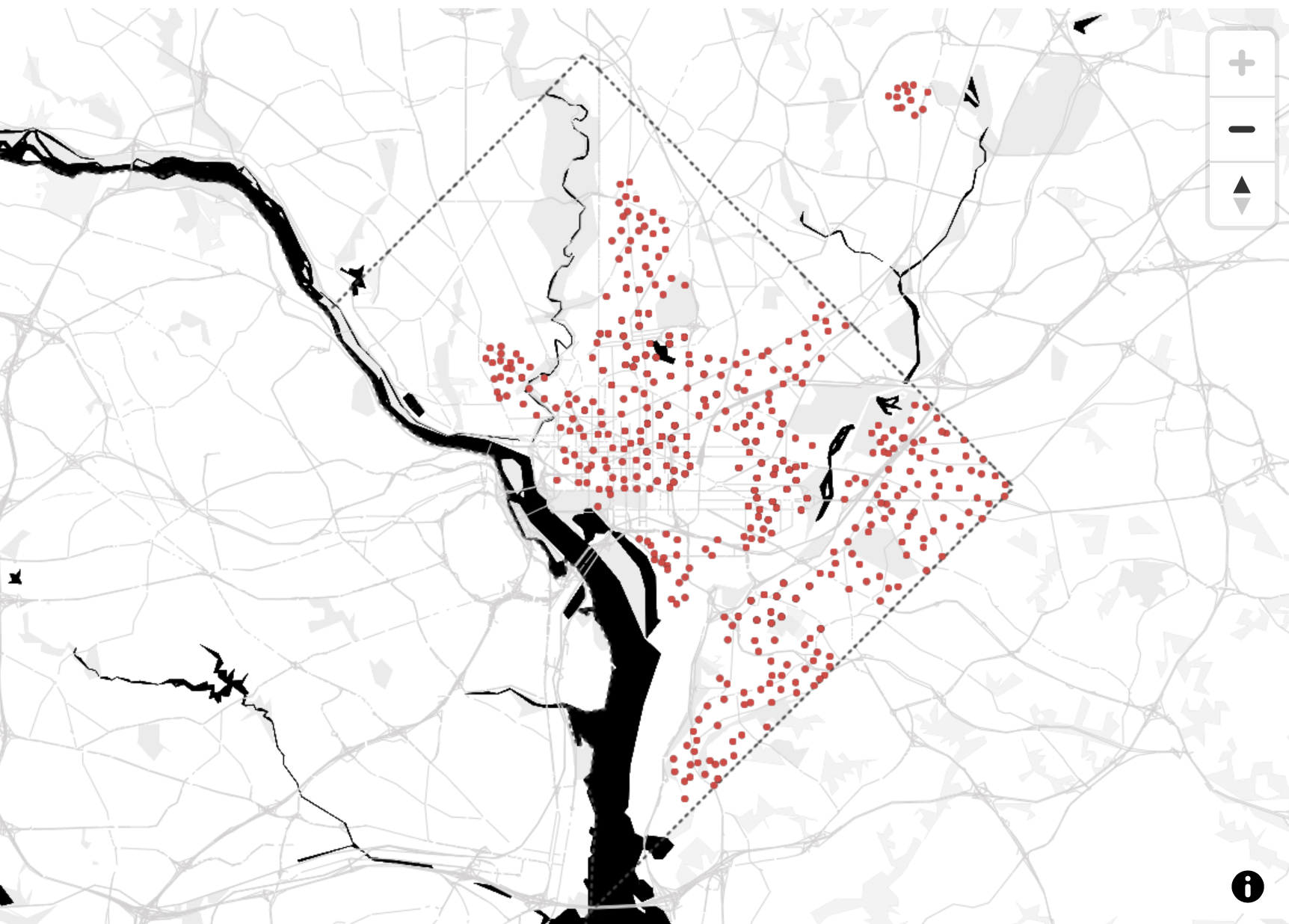

More than 12 million Americans live in neighborhoods with at least one ShotSpotter sensor, according to a WIRED analysis of the document’s sensor locations. According to the file, which includes the geographic coordinates of each ShotSpotter microphone, sensors can be found in 84 metropolitan areas and 34 states or territories in the United States. Nine cities have more than 500 sensors installed, including Albuquerque, New Mexico; Chicago, Illinois; Washington, DC; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Las Vegas, Nevada. The document does not indicate whether the list of sensors is comprehensive.

Using population estimates from the most recent five-year American Community Survey (ACS), WIRED collected demographic information from every Census block group—clusters of blocks that generally have a population of between 600 to 3,000 people—with at least one sensor.

An analysis of sensor distribution in US cities in the leaked data set found that, in aggregate, nearly 70 percent of people who live in a neighborhood with at least one SoundThinking sensor identified in the ACS data as either Black or Latine. Nearly three-quarters of these neighborhoods are majority nonwhite, and the average household earns a little more than $50,000 a year.

Looking at individual jurisdictions, the pattern appeared the same. Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for example, is approximately 43 percent white, but only 13 percent of the residents who live in areas that have at least one ShotSpotter device installed identify as white, according to ACS estimates. In Fort Myers, Florida, roughly 19 percent of the population is Black; in block groups with at least one sensor, however, approximately 41 percent of the population is Black.

In an interview, Tom Chittum, senior vice president of forensic services at SoundThinking, tells WIRED that he is “willing to accept that our findings are true” and confirmed that the document is likely authentic. A former associate deputy director of the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Chittum argues that SoundThinking sensors provide police departments with a commonsense resource to help combat gun violence. He claims that SoundThinking places the sensors in areas that are likely disproportionately impacted by gun violence, which helps police quickly get to the scene, especially when no emergency call is made to 911.

In September last year, a leading US-based civil liberties nonprofit, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), wrote a letter to the US Department of Justice, asking the agency to investigate whether cities using ShotSpotter are violating the Civil Rights Act. Citing news reports and academic studies, EPIC alleged that Sound Thinking’s sensors are directing law enforcement to over-police areas where the fewest number of white residents live.

According to Chittum, SoundThinking’s sensor deployment is not informed by race. The company asks police departments who purchase its system for data about gun violence, which Chittum characterizes as objective, to recommend a general plan for sensor placement. Once a plan is agreed upon by the department, the company will seek permission from private property owners, utility companies, and businesses to install sensors on their premises. While Chittum says that most property owners agree to do so without needing incentivization, the company will occasionally offer owners gift cards to secure access to their private property. According to SoundThinking, police are never told the precise location of the sensors that the company ultimately installs.

“I wish we were deployed everywhere,” Chittum says. “If you can only deploy a tool on a limited basis, of course, you deploy it in the place where it could do the greatest good.”

According to the file, 2,680 of SoundThinking sensors—one in 10—were categorized as either broken, unreliable, or out of service at the time the file was created, allegedly late last year.

In January, South Side Weekly reported that SoundThinking sensors in Chicago failed to issue an alert for a 55-round shooting at a gyro shop that wounded two men. According to internal company emails reviewed by the publication, the cause of the missed detections were three out-of-service sensors. According to the file, as many as 357 sensors in the Chicago Metropolitan Area were broken, unreliable, or out of service at the time the file was created—9 percent of the total.

While Chittum concedes that the company may occasionally miss gunshots, he argues that the presence of thousands of broken sensors doesn’t necessarily make the system unreliable. To ensure total coverage of an area, Chittum says, the company will strategically “oversaturate” an area with sensors. For a sound to be flagged as a gunshot, Chittum says, at least three sensors need to detect it; typically, Chittum says, a gunshot triggers a dozen or more sensors. “If one doesn’t catch it, others will,” he says.

The document provides a detailed snapshot of the company’s operations at the specific point in time that the file was created. We do not know if the sensors described in the document are still operational or not.

SoundThinking’s secrecy around the location of its sensors has long been a point of contention for activists and researchers. By 2019, at the recommendation of the Policing Project, a public safety nonprofit run out of New York University School of Law, the company adopted a policy that formally states that its clients cannot access the precise locations of their gunshot detection equipment. According to Chittum, the company will even resist subpoenas for information about the location of their sensors in court. The reason for this, according to Chittum, is for the security of the people who cooperate with SoundThinking as well as to protect their sensors from vandalism.

WIRED vetted the locations listed in the document by visiting sensors in two cities: Pasadena, California, and Newburgh, New York. WIRED also used Google Street View to virtually visit a random sample of locations listed in the document and found they matched the placement of equipment that appears to be SoundThinking’s.

In marketing material, SoundThinking claims that its gunshot-detection system has a 97 percent aggregate accuracy rate over a two-year period. Experts question those figures. A 2021 study conducted by the MacArthur Justice Center at the Northwestern University School of Law found that over two years, 89 percent of ShotSpotter alerts in the city did not lead to police finding evidence of a gun-related crime on arrival, such as shell casings. Recent investigations by both Knock LA and Houston Chronicle, have similarly raised doubts about the system's effectiveness. Both reports found that gunshot alerts triggered by the software largely resulted in dead ends for police.

Finding shell casings can be extremely difficult. A Los Angeles Police Department officer not authorized to speak to the media tells WIRED they’ve spent “hours” searching for bullet casings. Just because officers don’t find evidence of gunfire, they say, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Until now, the exact locations of SoundThinking’s sensors have been kept secret from both its police department clients and the public at large. A leaked document, which WIRED obtained from a source under the condition of anonymity, details the alleged precise locations and uptime of 25,580 ShotSpotter microphones. The data exposes for the first time the reach of SoundThinking’s network of surveillance devices and adds new context to an ongoing debate between activists and academics who claim ShotSpotter perpetuates biased policing practices and proponents of the technology.

According to the document, SoundThinking equipment has been installed at more than a thousand elementary and high schools; they are perched atop dozens of billboards, scores of hospitals, and within more than a hundred public housing complexes. They can be found on significant US government buildings, including the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Justice, and the US Court of Appeals in Washington, DC.

More than 12 million Americans live in neighborhoods with at least one ShotSpotter sensor, according to a WIRED analysis of the document’s sensor locations. According to the file, which includes the geographic coordinates of each ShotSpotter microphone, sensors can be found in 84 metropolitan areas and 34 states or territories in the United States. Nine cities have more than 500 sensors installed, including Albuquerque, New Mexico; Chicago, Illinois; Washington, DC; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Las Vegas, Nevada. The document does not indicate whether the list of sensors is comprehensive.

Using population estimates from the most recent five-year American Community Survey (ACS), WIRED collected demographic information from every Census block group—clusters of blocks that generally have a population of between 600 to 3,000 people—with at least one sensor.

An analysis of sensor distribution in US cities in the leaked data set found that, in aggregate, nearly 70 percent of people who live in a neighborhood with at least one SoundThinking sensor identified in the ACS data as either Black or Latine. Nearly three-quarters of these neighborhoods are majority nonwhite, and the average household earns a little more than $50,000 a year.

Looking at individual jurisdictions, the pattern appeared the same. Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for example, is approximately 43 percent white, but only 13 percent of the residents who live in areas that have at least one ShotSpotter device installed identify as white, according to ACS estimates. In Fort Myers, Florida, roughly 19 percent of the population is Black; in block groups with at least one sensor, however, approximately 41 percent of the population is Black.

In an interview, Tom Chittum, senior vice president of forensic services at SoundThinking, tells WIRED that he is “willing to accept that our findings are true” and confirmed that the document is likely authentic. A former associate deputy director of the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Chittum argues that SoundThinking sensors provide police departments with a commonsense resource to help combat gun violence. He claims that SoundThinking places the sensors in areas that are likely disproportionately impacted by gun violence, which helps police quickly get to the scene, especially when no emergency call is made to 911.

In September last year, a leading US-based civil liberties nonprofit, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), wrote a letter to the US Department of Justice, asking the agency to investigate whether cities using ShotSpotter are violating the Civil Rights Act. Citing news reports and academic studies, EPIC alleged that Sound Thinking’s sensors are directing law enforcement to over-police areas where the fewest number of white residents live.

According to Chittum, SoundThinking’s sensor deployment is not informed by race. The company asks police departments who purchase its system for data about gun violence, which Chittum characterizes as objective, to recommend a general plan for sensor placement. Once a plan is agreed upon by the department, the company will seek permission from private property owners, utility companies, and businesses to install sensors on their premises. While Chittum says that most property owners agree to do so without needing incentivization, the company will occasionally offer owners gift cards to secure access to their private property. According to SoundThinking, police are never told the precise location of the sensors that the company ultimately installs.

“I wish we were deployed everywhere,” Chittum says. “If you can only deploy a tool on a limited basis, of course, you deploy it in the place where it could do the greatest good.”

According to the file, 2,680 of SoundThinking sensors—one in 10—were categorized as either broken, unreliable, or out of service at the time the file was created, allegedly late last year.

In January, South Side Weekly reported that SoundThinking sensors in Chicago failed to issue an alert for a 55-round shooting at a gyro shop that wounded two men. According to internal company emails reviewed by the publication, the cause of the missed detections were three out-of-service sensors. According to the file, as many as 357 sensors in the Chicago Metropolitan Area were broken, unreliable, or out of service at the time the file was created—9 percent of the total.

While Chittum concedes that the company may occasionally miss gunshots, he argues that the presence of thousands of broken sensors doesn’t necessarily make the system unreliable. To ensure total coverage of an area, Chittum says, the company will strategically “oversaturate” an area with sensors. For a sound to be flagged as a gunshot, Chittum says, at least three sensors need to detect it; typically, Chittum says, a gunshot triggers a dozen or more sensors. “If one doesn’t catch it, others will,” he says.

The document provides a detailed snapshot of the company’s operations at the specific point in time that the file was created. We do not know if the sensors described in the document are still operational or not.

SoundThinking’s secrecy around the location of its sensors has long been a point of contention for activists and researchers. By 2019, at the recommendation of the Policing Project, a public safety nonprofit run out of New York University School of Law, the company adopted a policy that formally states that its clients cannot access the precise locations of their gunshot detection equipment. According to Chittum, the company will even resist subpoenas for information about the location of their sensors in court. The reason for this, according to Chittum, is for the security of the people who cooperate with SoundThinking as well as to protect their sensors from vandalism.

WIRED vetted the locations listed in the document by visiting sensors in two cities: Pasadena, California, and Newburgh, New York. WIRED also used Google Street View to virtually visit a random sample of locations listed in the document and found they matched the placement of equipment that appears to be SoundThinking’s.

In marketing material, SoundThinking claims that its gunshot-detection system has a 97 percent aggregate accuracy rate over a two-year period. Experts question those figures. A 2021 study conducted by the MacArthur Justice Center at the Northwestern University School of Law found that over two years, 89 percent of ShotSpotter alerts in the city did not lead to police finding evidence of a gun-related crime on arrival, such as shell casings. Recent investigations by both Knock LA and Houston Chronicle, have similarly raised doubts about the system's effectiveness. Both reports found that gunshot alerts triggered by the software largely resulted in dead ends for police.

Finding shell casings can be extremely difficult. A Los Angeles Police Department officer not authorized to speak to the media tells WIRED they’ve spent “hours” searching for bullet casings. Just because officers don’t find evidence of gunfire, they say, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.