Colleges

- American Athletic

- Atlantic Coast

- Big 12

- Big East

- Big Ten

- Colonial

- Conference USA

- Independents (FBS)

- Junior College

- Mountain West

- Northeast

- Pac-12

- Patriot League

- Pioneer League

- Southeastern

- Sun Belt

- Army

- Charlotte

- East Carolina

- Florida Atlantic

- Memphis

- Navy

- North Texas

- Rice

- South Florida

- Temple

- Tulane

- Tulsa

- UAB

- UTSA

- Boston College

- California

- Clemson

- Duke

- Florida State

- Georgia Tech

- Louisville

- Miami (FL)

- North Carolina

- North Carolina State

- Pittsburgh

- Southern Methodist

- Stanford

- Syracuse

- Virginia

- Virginia Tech

- Wake Forest

- Arizona

- Arizona State

- Baylor

- Brigham Young

- Cincinnati

- Colorado

- Houston

- Iowa State

- Kansas

- Kansas State

- Oklahoma State

- TCU

- Texas Tech

- UCF

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Michigan State

- Minnesota

- Nebraska

- Northwestern

- Ohio State

- Oregon

- Penn State

- Purdue

- Rutgers

- UCLA

- USC

- Washington

- Wisconsin

High Schools

- Illinois HS Sports

- Indiana HS Sports

- Iowa HS Sports

- Kansas HS Sports

- Michigan HS Sports

- Minnesota HS Sports

- Missouri HS Sports

- Nebraska HS Sports

- Oklahoma HS Sports

- Texas HS Hoops

- Texas HS Sports

- Wisconsin HS Sports

- Cincinnati HS Sports

- Delaware

- Maryland HS Sports

- New Jersey HS Hoops

- New Jersey HS Sports

- NYC HS Hoops

- Ohio HS Sports

- Pennsylvania HS Sports

- Virginia HS Sports

- West Virginia HS Sports

ADVERTISEMENT

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Filters

Show only:

Davenport church forgives man who robbed them

QC nice

Login to view embedded media

On the cover of the Sunday, May 26 bulletin at Davenport’s Zion Lutheran Church, parishioners could read a heartfelt letter from the young man who broke in and robbed their house of worship last month.

Writing from Scott County Jail, 24-year-old Trenton Stewart apologized to the congregation, after receiving many notes from church members.

One such note from a Zion member said in part: “The role of the church is love, grace and forgiveness. I am sorry there are conditions in your life that led you to take from our church. You are welcome here.”

The following letter—handwritten by Stewart and dated May 7—was delivered to Zion Monday, May 20:

“I know you guys did not deserve that at all. No matter how much I want to put it on a heavy drug addiction… The truth is that I let the devil into my heart. No matter what I was wrong. I never would of imagined to receive a letter from you guys… I’m in my cell now writing this letter feeling guilty but very loved at the same time. Thank you so much, I really loved all of the notes you have wrote me!!

“Even though I was in a tough situation… I also know I put myself into that tough situation… I’m just sorry that I brought my troubles unto all of you guys and destroyed your guys church all at the same time.

“I’m honestly expecting to go to prison for all of this and I know God will be with me during this as long as I stay strong in faith in him.

“I absolutely know and understand if not, but I really don’t have nobody, my mom is the only I but she is in a abusive relationship… Anyways she really can’t because he’ll flip-out on my mom but if you would be able to help me out with a few bucks on my books that would be if not amazing.

“I’m understanding completely if not… I know my Grandpa “David” was Lutheran and he used to say “Ask & you shall receive” but he also used to say “The Golden Rule: Treat ppl the way that you want to be treated” And for that I am sorry for not following The Golden Rule… I am deeply sorry & would love to keep writing letters back & forth, it made at least my world a little brighter when I got some mail thank you.”

Stewart drew a heart and inside, he wrote:

“Thank you for writing me hopefully I will hear back soon.

Please keep me in your guys prayers!

Please send more encouraging notes.

Please teach me more about God, it’s pretty dark in here.

Thank you for not judging me nor hating me… I promise I’m a good person just lost sometimes…”

Stewart was in custody that Saturday, April 27, and he faces a felony charge of third-degree burglary, an aggravated misdemeanor charge of third-degree theft and a serious misdemeanor charge of fourth-degree criminal mischief, according to arrest affidavits.

Olson-Smith said the church has recovered a few items that were stolen, including parts of the security system, but two laptops are gone, and the church has replaced stolen microphones. It has submitted an insurance claim valued at $15,000.

During worship on Sunday, May 5, Zion people wrote to Stewart in Scott County Jail.

“I’ve felt strongly that I myself wanted to reach out to him and I wasn’t quite sure what to say,” Olson-Smith said Tuesday, stressing forgiveness and second chances. He invited church members to write notes to Stewart, and about 30 did, offering compassion, support and forgiveness.

Olson-Smith said one of the problems with the criminal justice system in general is that “it separates us at a time when there’s an opportunity to bring people together. I would hope that healing is the goal and not just punishment, right?” he said. “He’s likely going to prison and who knows for how long, you know? He’s not really paying a debt to Zion by going to prison,” the pastor said.

“At least there could be some reconciliation. I think the line that really stuck out to me from his letter was — I’m sitting here in my cell now writing to you feeling guilty and very loved. And that’s kind of the thing that’s the beginning of what I hope is the ability for him to change his life.”

Moved by response

Olson-Smith said many church members were very moved by Stewart’s response. “Just to hear anything at all felt like a small miracle,” he said. “I could imagine a response of like, ‘screw these guys’ and he would throw it in the trash.”

“There at the end, he asked us to keep sending encouraging notes and he said, ‘Please keep teaching me about God. It’s dark in here’,” Olson-Smith said. “It’s just heartbreaking, you know, heartbreaking.”

n a May 21 letter to Stewart (after receiving his response), the pastor encouraged him to turn his life around.

“God brings life out of death and good out of bad,” Olson-Smith wrote. “Today’s mistakes can be tomorrow’s testimony about the forgiveness and saving power of Jesus.”

“Jesus was always where suffering was, and Jesus healed people in the here and now,” his letter said. “Christians sometimes push that healing down the road to some distant future and reserve it only for the ‘worthy.’ But that was not Jesus’s way, which was a big part of his conflict with the religious leaders of his day. Jesus healed anyone who really wanted to be healed, and that was too much for people who thought they didn’t need any healing.”

Among his arrest record, in April 2021, at age 21 Stewart was charged with burglary and theft after breaking into a home in the 1900 block of W. 36th Street, Davenport, using a screwdriver and other tools. He entered a locked garage, then went into the residence and retrieved the keys for the vehicle in the garage.

Last month, police allege that, once Stewart was inside the Probstei Inn (6315 W. Kimberly Rd., Davenport), he stole various business checks belonging to Probstei Inn, along with a safe.

An hour later on the same day, court records say, Davenport Police responded to CBI Bank & Trust, 2322 E. Kimberly Road, Davenport, in reference to fraud. Arrest affidavits say Stewart entered CBI Bank & Trust with a forged check belonging to Probstei Inn. Court records say the defendant did this twice at different times, and was captured on surveillance footage.

Login to view embedded media

On the cover of the Sunday, May 26 bulletin at Davenport’s Zion Lutheran Church, parishioners could read a heartfelt letter from the young man who broke in and robbed their house of worship last month.

Writing from Scott County Jail, 24-year-old Trenton Stewart apologized to the congregation, after receiving many notes from church members.

One such note from a Zion member said in part: “The role of the church is love, grace and forgiveness. I am sorry there are conditions in your life that led you to take from our church. You are welcome here.”

The following letter—handwritten by Stewart and dated May 7—was delivered to Zion Monday, May 20:

“I know you guys did not deserve that at all. No matter how much I want to put it on a heavy drug addiction… The truth is that I let the devil into my heart. No matter what I was wrong. I never would of imagined to receive a letter from you guys… I’m in my cell now writing this letter feeling guilty but very loved at the same time. Thank you so much, I really loved all of the notes you have wrote me!!

“Even though I was in a tough situation… I also know I put myself into that tough situation… I’m just sorry that I brought my troubles unto all of you guys and destroyed your guys church all at the same time.

“I’m honestly expecting to go to prison for all of this and I know God will be with me during this as long as I stay strong in faith in him.

“I absolutely know and understand if not, but I really don’t have nobody, my mom is the only I but she is in a abusive relationship… Anyways she really can’t because he’ll flip-out on my mom but if you would be able to help me out with a few bucks on my books that would be if not amazing.

“I’m understanding completely if not… I know my Grandpa “David” was Lutheran and he used to say “Ask & you shall receive” but he also used to say “The Golden Rule: Treat ppl the way that you want to be treated” And for that I am sorry for not following The Golden Rule… I am deeply sorry & would love to keep writing letters back & forth, it made at least my world a little brighter when I got some mail thank you.”

Stewart drew a heart and inside, he wrote:

“Thank you for writing me hopefully I will hear back soon.

Please keep me in your guys prayers!

Please send more encouraging notes.

Please teach me more about God, it’s pretty dark in here.

Thank you for not judging me nor hating me… I promise I’m a good person just lost sometimes…”

Stewart was in custody that Saturday, April 27, and he faces a felony charge of third-degree burglary, an aggravated misdemeanor charge of third-degree theft and a serious misdemeanor charge of fourth-degree criminal mischief, according to arrest affidavits.

Olson-Smith said the church has recovered a few items that were stolen, including parts of the security system, but two laptops are gone, and the church has replaced stolen microphones. It has submitted an insurance claim valued at $15,000.

During worship on Sunday, May 5, Zion people wrote to Stewart in Scott County Jail.

“I’ve felt strongly that I myself wanted to reach out to him and I wasn’t quite sure what to say,” Olson-Smith said Tuesday, stressing forgiveness and second chances. He invited church members to write notes to Stewart, and about 30 did, offering compassion, support and forgiveness.

Olson-Smith said one of the problems with the criminal justice system in general is that “it separates us at a time when there’s an opportunity to bring people together. I would hope that healing is the goal and not just punishment, right?” he said. “He’s likely going to prison and who knows for how long, you know? He’s not really paying a debt to Zion by going to prison,” the pastor said.

“At least there could be some reconciliation. I think the line that really stuck out to me from his letter was — I’m sitting here in my cell now writing to you feeling guilty and very loved. And that’s kind of the thing that’s the beginning of what I hope is the ability for him to change his life.”

Moved by response

Olson-Smith said many church members were very moved by Stewart’s response. “Just to hear anything at all felt like a small miracle,” he said. “I could imagine a response of like, ‘screw these guys’ and he would throw it in the trash.”

“There at the end, he asked us to keep sending encouraging notes and he said, ‘Please keep teaching me about God. It’s dark in here’,” Olson-Smith said. “It’s just heartbreaking, you know, heartbreaking.”

n a May 21 letter to Stewart (after receiving his response), the pastor encouraged him to turn his life around.

“God brings life out of death and good out of bad,” Olson-Smith wrote. “Today’s mistakes can be tomorrow’s testimony about the forgiveness and saving power of Jesus.”

“Jesus was always where suffering was, and Jesus healed people in the here and now,” his letter said. “Christians sometimes push that healing down the road to some distant future and reserve it only for the ‘worthy.’ But that was not Jesus’s way, which was a big part of his conflict with the religious leaders of his day. Jesus healed anyone who really wanted to be healed, and that was too much for people who thought they didn’t need any healing.”

Among his arrest record, in April 2021, at age 21 Stewart was charged with burglary and theft after breaking into a home in the 1900 block of W. 36th Street, Davenport, using a screwdriver and other tools. He entered a locked garage, then went into the residence and retrieved the keys for the vehicle in the garage.

Last month, police allege that, once Stewart was inside the Probstei Inn (6315 W. Kimberly Rd., Davenport), he stole various business checks belonging to Probstei Inn, along with a safe.

An hour later on the same day, court records say, Davenport Police responded to CBI Bank & Trust, 2322 E. Kimberly Road, Davenport, in reference to fraud. Arrest affidavits say Stewart entered CBI Bank & Trust with a forged check belonging to Probstei Inn. Court records say the defendant did this twice at different times, and was captured on surveillance footage.

Trump pledges to turn ‘love it or leave it’ into policy

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 4 Replies

Americans tend to approve of the right to protest more in the abstract than when manifested. For decades, public protest often triggered an exaggerated reaction: If you don’t like how things are in the United States, get out. Particularly since the Vietnam War, this response has often been partisan, with members of the political right encouraging the frustrated left to simply leave.

Cut through the 2024 election noise. Get The Campaign Moment newsletter.

Donald Trump’s tendency to reflect and amplify rhetorical extremes has led him to propose a formal instantiation of this idea, should he be reelected president. If he returns to the White House, he promised to donors at a recent event, he would “set [the anti-Israel] movement back 25 or 30 years.”

Skip to end of carousel

End of carousel

How? In part by deporting those who participate in protests on college campuses.

“One thing I do is, any student that protests, I throw them out of the country,” he said, according to reporting from The Washington Post’s Josh Dawsey, Karen DeYoung and Marianne LeVine. “You know, there are a lot of foreign students. As soon as they hear that, they’re going to behave.”

There are foreign students in American universities. About 5 percent of students were from foreign countries at the beginning of 2022, though only about a quarter of a percent were from the Middle East and North Africa, the region that’s long been a focus of Trump’s fearmongering. But those are students in total, not students at recent campus protests. While some of those involved in the protests have been noncitizens, there’s no reason to think that most or even a significant portion of them were. But there’s also no reason to think Trump is particularly concerned about that technicality.

Follow Election 2024

In October, the Trump campaign unveiled its “plan to keep jihadists and their sympathizers out of America” — an early formulation of Trump’s eager effort to demonstrate his hostility to critics of Israel’s response to the terrorist attack that month. Among its elements:

Another is that “jihadist sympathies” not only describes a lot of protected speech, it is entirely subjective.

“If you hate America, if you want to abolish Israel, if you sympathize with jihadists,” Trump said during a December speech in Nevada, “then we don’t want you in our country. We don’t want you.”

Those are three very different categories, but the blurring is intentional. The promise Trump is offering is one that’s been tantalizing the right for decades: love it or leave it as federal policy.

The most alarming aspect of Trump’s proposal is the deployment of federal immigration officers to protests to police speech. It should not be a consolation that the target of that ICE supervision is immigrants, even setting aside free speech issues. Such a policy would almost certainly mean detentions of U.S. citizens and eventual deportations.

This is not hyperbolic. An analysis conducted by the Government Accountability Office determined that hundreds of likely U.S. citizens were detained by immigration officials during Trump’s presidency and that dozens were deported. That number includes at least five children.

It is not unique to the Trump administration that citizens should be swept up in the immigration process. The GAO’s analysis found that more than 260 likely citizens were arrested in fiscal 2015 and 2016, under President Barack Obama. Only four citizens were removed from the country in that period, however. From fiscal 2017 (which overlapped with Obama’s administration) to the first two quarters of fiscal 2020, 50 men and 15 women were removed from the United States despite being identified as citizens of or having been born in the United States.

There are checks in place to protect citizens from being deported, but those can occur after the person is already in custody. If there is evidence of citizenship or uncertainty about status, the person is supposed to be released or (if not yet in custody) not arrested. Yet it’s likely that dozens of Americans were deported by the Trump administration anyway. In a scenario where immigration officers are more empowered to seek out targets, a small rate of failure could mean far more improper deportations.

It’s certainly possible that a newly reelected Trump would not implement this proposal; his track record of effecting his most extreme promises is spotty. He was speaking to donors hostile to the campus protests in the comments reported by The Post, meaning that he was, in a way, making a sales pitch for his candidacy. Trump has at times not followed through for his customers.

It’s also possible that courts would block immigration actions centered on speech or impose guardrails meant to protect U.S. citizens. Trump’s 2015 campaign-trail pledge to block immigrants from Muslim countries, though, ended up being upheld by the Supreme Court. Reintroducing such a ban was the first item on the Trump campaign’s list of promises for keeping “jihadists” out of America.

This exploration of possible worst-case scenarios should not distract from Trump’s comments in the moment. He pledged to supporters that he would hobble a protest movement with which he disagrees, in part, by leveraging federal law enforcement against the protesters. Should he be reelected and force the Supreme Court to consider whether his implementation of this idea is valid, he’s already largely achieved his intended goal.

Cut through the 2024 election noise. Get The Campaign Moment newsletter.

Donald Trump’s tendency to reflect and amplify rhetorical extremes has led him to propose a formal instantiation of this idea, should he be reelected president. If he returns to the White House, he promised to donors at a recent event, he would “set [the anti-Israel] movement back 25 or 30 years.”

Skip to end of carousel

Sign up for the How to Read This Chart newsletter

Subscribe to How to Read This Chart, a weekly dive into the data behind the news. Each Saturday, national columnist Philip Bump makes and breaks down charts explaining the latest in economics, pop culture, politics and more.End of carousel

How? In part by deporting those who participate in protests on college campuses.

“One thing I do is, any student that protests, I throw them out of the country,” he said, according to reporting from The Washington Post’s Josh Dawsey, Karen DeYoung and Marianne LeVine. “You know, there are a lot of foreign students. As soon as they hear that, they’re going to behave.”

There are foreign students in American universities. About 5 percent of students were from foreign countries at the beginning of 2022, though only about a quarter of a percent were from the Middle East and North Africa, the region that’s long been a focus of Trump’s fearmongering. But those are students in total, not students at recent campus protests. While some of those involved in the protests have been noncitizens, there’s no reason to think that most or even a significant portion of them were. But there’s also no reason to think Trump is particularly concerned about that technicality.

Follow Election 2024

In October, the Trump campaign unveiled its “plan to keep jihadists and their sympathizers out of America” — an early formulation of Trump’s eager effort to demonstrate his hostility to critics of Israel’s response to the terrorist attack that month. Among its elements:

- “aggressively deport resident aliens with jihadist sympathies”

- “revoke the student visas of radical anti-American and antisemitic foreigners at colleges and universities”

- “proactively send [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] to pro-jihadist demonstrations to enforce our immigration laws and remove the violators from our country”

Another is that “jihadist sympathies” not only describes a lot of protected speech, it is entirely subjective.

“If you hate America, if you want to abolish Israel, if you sympathize with jihadists,” Trump said during a December speech in Nevada, “then we don’t want you in our country. We don’t want you.”

Those are three very different categories, but the blurring is intentional. The promise Trump is offering is one that’s been tantalizing the right for decades: love it or leave it as federal policy.

The most alarming aspect of Trump’s proposal is the deployment of federal immigration officers to protests to police speech. It should not be a consolation that the target of that ICE supervision is immigrants, even setting aside free speech issues. Such a policy would almost certainly mean detentions of U.S. citizens and eventual deportations.

This is not hyperbolic. An analysis conducted by the Government Accountability Office determined that hundreds of likely U.S. citizens were detained by immigration officials during Trump’s presidency and that dozens were deported. That number includes at least five children.

It is not unique to the Trump administration that citizens should be swept up in the immigration process. The GAO’s analysis found that more than 260 likely citizens were arrested in fiscal 2015 and 2016, under President Barack Obama. Only four citizens were removed from the country in that period, however. From fiscal 2017 (which overlapped with Obama’s administration) to the first two quarters of fiscal 2020, 50 men and 15 women were removed from the United States despite being identified as citizens of or having been born in the United States.

There are checks in place to protect citizens from being deported, but those can occur after the person is already in custody. If there is evidence of citizenship or uncertainty about status, the person is supposed to be released or (if not yet in custody) not arrested. Yet it’s likely that dozens of Americans were deported by the Trump administration anyway. In a scenario where immigration officers are more empowered to seek out targets, a small rate of failure could mean far more improper deportations.

It’s certainly possible that a newly reelected Trump would not implement this proposal; his track record of effecting his most extreme promises is spotty. He was speaking to donors hostile to the campus protests in the comments reported by The Post, meaning that he was, in a way, making a sales pitch for his candidacy. Trump has at times not followed through for his customers.

It’s also possible that courts would block immigration actions centered on speech or impose guardrails meant to protect U.S. citizens. Trump’s 2015 campaign-trail pledge to block immigrants from Muslim countries, though, ended up being upheld by the Supreme Court. Reintroducing such a ban was the first item on the Trump campaign’s list of promises for keeping “jihadists” out of America.

This exploration of possible worst-case scenarios should not distract from Trump’s comments in the moment. He pledged to supporters that he would hobble a protest movement with which he disagrees, in part, by leveraging federal law enforcement against the protesters. Should he be reelected and force the Supreme Court to consider whether his implementation of this idea is valid, he’s already largely achieved his intended goal.

Have you ever had an account hacked online?

- By BrianNole777

- Off Topic

- 25 Replies

I just got an email saying 8 of my online passwords have been compromised so I changed them.

I imagine if I got hacked, some real damage could have been done.

Have you ever been hacked? What happened?

I imagine if I got hacked, some real damage could have been done.

Have you ever been hacked? What happened?

Prominent pollster spreads Dominion voting machine misinformation

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 5 Replies

“Is it possible that @dominionvoting is admitting to something in court that they thus far have NOT admitted to their US contract clients & millions of voters? The American electorate deserves to know. And right now please.”

Cut through the 2024 election noise. Get The Campaign Moment newsletter.

— Social media account of Rasmussen Reports, which describes itself as a nonpartisan electronic media company that conducts polls, May 17

With almost a half million followers on X, the pollster Rasmussen has a wide reach. Former president Donald Trump repeatedly cited its polls when he was president as it consistently showed a higher approval rating for him than other pollsters.

Now Rasmussen’s social media account is fanning previously debunked claims that Dominion Voting Systems machines could somehow be manipulated via the internet.

Rasmussen’s source is a former Michigan state senator who traffics in election conspiracy theories and is president of a self-described election integrity group called the Michigan Grassroots Alliance. That former lawmaker cited emails released by a far-right sheriff, who obtained them from an attorney involved in a lawsuit filed by Dominion, despite a protective order agreed to by the parties in the case.

Confused? That’s part of the point. The idea is to create a lot of smoke to make people think there is a fire.

For instance, Colbeck was featured in a 93-minute video that circulated online in December 2020 in which he repeated the false claim that the machines that counted paper ballots were connected to the internet and inaccurately suggested the tabulators could have been hacked. That claim had already been rejected by Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Timothy M. Kenny, who in an opinion rejected an affidavit filed by Colbeck. “No evidence supports Mr. Colbeck’s position,” Kenny wrote. He noted that in a Facebook post before the election, Colbeck said that Democrats were using the pandemic as a cover for fraud, which Kenny said “undermines his credibility as a witness.”

That didn’t deter Colbeck, who continued making so many claims about Dominion that the company in 2021 sent a letter hinting at legal action if he didn’t stop making the claims.

Follow Election 2024

“You successfully duped thousands of people across Michigan into believing that the 2020 election was stolen through the manipulation of vote counts in Dominion machines, and you have reaped the benefits from it,” Dominion attorneys said in a letter. The missive suggested that the company — which won a $787 million settlement from Fox News and has pursued claims against other election deniers — might take legal action. No lawsuit has yet been filed.

Now Colbeck is claiming vindication. On X, he claimed that in court proceedings, Dominion authenticated documents that show “Dominion machines are designed to connect to internet” and “Dominion employs Serbian developers not subject to thorough background checks.” He added: “We’ve been lied to for years. Now the truth is FINALLY being exposed … IN COURT!” This was one of the posts that Rasmussen Reports circulated to its followers, suggesting Dominion has misled clients and millions of voters.

The documents were released by Sheriff Dar Leaf of Barry County, who posted them on the internet. Stefanie Lambert, a lawyer for former Overstock chief executive Patrick Byrne, has said she gave them to Leaf, alleging they showed evidence of criminal activity. Dominion has filed a billion-dollar defamation suit against Byrne and is now seeking to have Lambert removed from the case for allegedly violating a protective order regarding discovery. “These documents are now being used for the specific purpose of spreading yet more lies about Dominion,” the company said in a legal filing.

Lambert has justified releasing the documents by arguing that Dominion had “inappropriately” abused the existing protective order to hide “law violations” by designating documents as “confidential trade secret/intellectual property.” Federal Magistrate Judge Moxila Upadhyaya, in a hearing in Washington on May 16, ordered Lambert to make every effort to remove leaked documents from social media and other public forums, according to the Detroit News. The judge emphasized that the protective order in the case barred the sharing of confidential documents.

Cut through the 2024 election noise. Get The Campaign Moment newsletter.

— Social media account of Rasmussen Reports, which describes itself as a nonpartisan electronic media company that conducts polls, May 17

With almost a half million followers on X, the pollster Rasmussen has a wide reach. Former president Donald Trump repeatedly cited its polls when he was president as it consistently showed a higher approval rating for him than other pollsters.

Now Rasmussen’s social media account is fanning previously debunked claims that Dominion Voting Systems machines could somehow be manipulated via the internet.

Rasmussen’s source is a former Michigan state senator who traffics in election conspiracy theories and is president of a self-described election integrity group called the Michigan Grassroots Alliance. That former lawmaker cited emails released by a far-right sheriff, who obtained them from an attorney involved in a lawsuit filed by Dominion, despite a protective order agreed to by the parties in the case.

Confused? That’s part of the point. The idea is to create a lot of smoke to make people think there is a fire.

The Facts

The 2020 presidential contest in Michigan was not especially close. Joe Biden defeated Trump by about 155,000 votes, a margin of almost three percentage points. Yet ever since, former Michigan state senator Patrick Colbeck (R) has made baseless claims about fraud in the presidential election. (He was a term-limited senator when he lost the Republican primary for governor in 2018.) He has especially aimed his ire at Dominion Voting Systems, which has a contract in some counties in the state.For instance, Colbeck was featured in a 93-minute video that circulated online in December 2020 in which he repeated the false claim that the machines that counted paper ballots were connected to the internet and inaccurately suggested the tabulators could have been hacked. That claim had already been rejected by Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Timothy M. Kenny, who in an opinion rejected an affidavit filed by Colbeck. “No evidence supports Mr. Colbeck’s position,” Kenny wrote. He noted that in a Facebook post before the election, Colbeck said that Democrats were using the pandemic as a cover for fraud, which Kenny said “undermines his credibility as a witness.”

That didn’t deter Colbeck, who continued making so many claims about Dominion that the company in 2021 sent a letter hinting at legal action if he didn’t stop making the claims.

Follow Election 2024

“You successfully duped thousands of people across Michigan into believing that the 2020 election was stolen through the manipulation of vote counts in Dominion machines, and you have reaped the benefits from it,” Dominion attorneys said in a letter. The missive suggested that the company — which won a $787 million settlement from Fox News and has pursued claims against other election deniers — might take legal action. No lawsuit has yet been filed.

Now Colbeck is claiming vindication. On X, he claimed that in court proceedings, Dominion authenticated documents that show “Dominion machines are designed to connect to internet” and “Dominion employs Serbian developers not subject to thorough background checks.” He added: “We’ve been lied to for years. Now the truth is FINALLY being exposed … IN COURT!” This was one of the posts that Rasmussen Reports circulated to its followers, suggesting Dominion has misled clients and millions of voters.

The documents were released by Sheriff Dar Leaf of Barry County, who posted them on the internet. Stefanie Lambert, a lawyer for former Overstock chief executive Patrick Byrne, has said she gave them to Leaf, alleging they showed evidence of criminal activity. Dominion has filed a billion-dollar defamation suit against Byrne and is now seeking to have Lambert removed from the case for allegedly violating a protective order regarding discovery. “These documents are now being used for the specific purpose of spreading yet more lies about Dominion,” the company said in a legal filing.

Lambert has justified releasing the documents by arguing that Dominion had “inappropriately” abused the existing protective order to hide “law violations” by designating documents as “confidential trade secret/intellectual property.” Federal Magistrate Judge Moxila Upadhyaya, in a hearing in Washington on May 16, ordered Lambert to make every effort to remove leaked documents from social media and other public forums, according to the Detroit News. The judge emphasized that the protective order in the case barred the sharing of confidential documents.

Pooping in a car

I know it’s not uncommon to have a pee bottle for long road trips, but it’s anybody pooped in their car?

Reynolds: Trump Trial a sham, egregious

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 29 Replies

What a POS she is:

Governor Kim Reynolds has not spoken to Iowa Attorney General Brenna Bird since Bird attended former President Donald Trump’s trial in New York on Monday, but both Reynolds and Bird are using the word “travesty” to describe the proceedings.

“It should be stopped. If this was anybody else, this wouldn’t be happening,” Reynolds said on Wednesday after a bill signing ceremony on an Iowa County farm. “It’s preventing him from being on the campaign trail.”

Reynolds said it’s important for fellow Republicans to attend the trial because the judge has ordered Trump not to speak about the jury, the prosecution or witnesses. “Other people have said, ‘Well then we’re going to go express our First Amendment right because we can say that this is a sham. There is no ‘there’ there,'” Reynolds said. “…And if they think this was going to take him down, I think it’s actually having the opposite impact.”

Reynolds, who has two dozen bills left from the 2024 legislative session to review and sign, told reporters from Radio Iowa and Iowa Public Radio she is focused on that and has no plan to fly to New York for the trial, but the governor said she intends to make it clear to Iowans how she views the case against Trump.

“This is ridiculous. It is a sham. It’s an egregious act that’s taking place and however you feel comfortable in helping relay that to the American people or to your constituents, that’s an individual decision,” Reynolds said, “but I think I’ve been pretty clear on where I stand with it.”

Trump was first charged over a year ago with making so-called “hush money” payments to prevent two women from publicly accusing him of having sex outside of his marriage. Reynolds, who backed Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in January’s Iowa Caucuses, endorsed Trump in early March, right after Trump won the so-called “Super Tuesday” primaries in 15 states.

Attorney General Bird endorsed Trump in October and her travel to Trump’s trial this week was paid for by the Republican Attorneys General Association. Reynolds, a member of the Republican Governors Association’s executive committee, said she’s not aware of similar arrangements being made by that group to get GOP governors to appear with Trump at the New York City courthouse.

www.radioiowa.com

www.radioiowa.com

Governor Kim Reynolds has not spoken to Iowa Attorney General Brenna Bird since Bird attended former President Donald Trump’s trial in New York on Monday, but both Reynolds and Bird are using the word “travesty” to describe the proceedings.

“It should be stopped. If this was anybody else, this wouldn’t be happening,” Reynolds said on Wednesday after a bill signing ceremony on an Iowa County farm. “It’s preventing him from being on the campaign trail.”

Reynolds said it’s important for fellow Republicans to attend the trial because the judge has ordered Trump not to speak about the jury, the prosecution or witnesses. “Other people have said, ‘Well then we’re going to go express our First Amendment right because we can say that this is a sham. There is no ‘there’ there,'” Reynolds said. “…And if they think this was going to take him down, I think it’s actually having the opposite impact.”

Reynolds, who has two dozen bills left from the 2024 legislative session to review and sign, told reporters from Radio Iowa and Iowa Public Radio she is focused on that and has no plan to fly to New York for the trial, but the governor said she intends to make it clear to Iowans how she views the case against Trump.

“This is ridiculous. It is a sham. It’s an egregious act that’s taking place and however you feel comfortable in helping relay that to the American people or to your constituents, that’s an individual decision,” Reynolds said, “but I think I’ve been pretty clear on where I stand with it.”

Trump was first charged over a year ago with making so-called “hush money” payments to prevent two women from publicly accusing him of having sex outside of his marriage. Reynolds, who backed Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in January’s Iowa Caucuses, endorsed Trump in early March, right after Trump won the so-called “Super Tuesday” primaries in 15 states.

Attorney General Bird endorsed Trump in October and her travel to Trump’s trial this week was paid for by the Republican Attorneys General Association. Reynolds, a member of the Republican Governors Association’s executive committee, said she’s not aware of similar arrangements being made by that group to get GOP governors to appear with Trump at the New York City courthouse.

Iowa's Governor says it's important for Republicans to attend Trump's trial - Radio Iowa

Governor Kim Reynolds has not spoken to Iowa Attorney General Brenna Bird since Bird attended former President Donald Trump’s trial in New York on Monday, but both Reynolds and Bird are using the word “travesty” to describe the proceedings. “It should be stopped. If this was anybody else, this...

Women's basketball assistant coaches

- By GunnerHawk

- Iowa Men's Basketball

- 12 Replies

So Jan has one or two positions to fill? Someone to replace her position and then someone to replace Jenn's special assistant role (or does that go away). Must be looking outside for her position.

Hard film scenes to watch....

- Off Topic

- 84 Replies

Fatal Attraction grabbed you and squeezed until it hurt. This scene. Wow.

Login to view embedded media

Login to view embedded media

Pooping in a bar

Csb I went to happy hour and went to rock a piss, and a guy didn't lock the single toilet bathroom door and he was taking a shit at 4 pm at a bar. Who does that?

When was the last time you pooped in a bar?

When was the last time you pooped in a bar?

Not The Onion

But the headline sure reads like an Onion article.

Tue, May 28, 2024 at 7:42 AM CDT·2 min read

Darien Harris was 12 years into a 76-year prison sentence when he was freed in December 2023 - Tyler Pasciak LaRiviere/Chicago Sun-Times

A man who spent 12 years in prison for murder is suing Chicago police after being convicted on an eyewitness account from a blind person.

Darien Harris was serving a 76-year sentence when he was freed in December after The Exoneration Project, an Chicago-based organisation fighting for the rights of the wrongly convicted, showed that the eyewitness had advanced glaucoma and had lied about his eyesight issues.

Despite being declared legally blind by his doctor nine years before the incident, the eyewitness picked Mr Harris out of a lineup and identified him in court.

The witness testified that he saw Mr Harris riding a motorised scooter near the gas station when he heard gunshots and saw a person aiming a handgun. He also claimed the shooter bumped into him.

The judge convicted Mr Harris, then an 18-year-old student, in connection with the fatal shooting at a gas station in 2011 in South Side Chicago.

When asked by Mr Harris’s lawyer whether his diabetes affected his vision, the witness said yes but denied that he had vision problems.

However, court records show that the man had been declared legally blind almost a decade before the start of the trial. A petrol station attendant also testified that Mr Harris was not the shooter.

Now 30 years old, he told the Chicago Tribune he is still struggling to put his life back together.

“I don’t have any financial help. I’m still [treated like] a felon, so I can’t get a good job. It’s hard for me to get into school,” he said.

“I’ve been so lost. I feel like they took a piece of me that is hard for me to get back.”

The Exoneration Project has helped clear the names of more than 200 people since 2009, including a dozen in Chicago’s Cook County in 2023 alone.

www.yahoo.com

www.yahoo.com

Man convicted of murder sues Chicago police after eyewitness revealed to be blind

Lorna PettyTue, May 28, 2024 at 7:42 AM CDT·2 min read

Darien Harris was 12 years into a 76-year prison sentence when he was freed in December 2023 - Tyler Pasciak LaRiviere/Chicago Sun-Times

A man who spent 12 years in prison for murder is suing Chicago police after being convicted on an eyewitness account from a blind person.

Darien Harris was serving a 76-year sentence when he was freed in December after The Exoneration Project, an Chicago-based organisation fighting for the rights of the wrongly convicted, showed that the eyewitness had advanced glaucoma and had lied about his eyesight issues.

Despite being declared legally blind by his doctor nine years before the incident, the eyewitness picked Mr Harris out of a lineup and identified him in court.

The witness testified that he saw Mr Harris riding a motorised scooter near the gas station when he heard gunshots and saw a person aiming a handgun. He also claimed the shooter bumped into him.

The judge convicted Mr Harris, then an 18-year-old student, in connection with the fatal shooting at a gas station in 2011 in South Side Chicago.

When asked by Mr Harris’s lawyer whether his diabetes affected his vision, the witness said yes but denied that he had vision problems.

However, court records show that the man had been declared legally blind almost a decade before the start of the trial. A petrol station attendant also testified that Mr Harris was not the shooter.

‘I’ve been so lost’

Mr Harris filed a federal civil rights lawsuit in April alleging that police fabricated evidence and coerced witnesses into making false statements.Now 30 years old, he told the Chicago Tribune he is still struggling to put his life back together.

“I don’t have any financial help. I’m still [treated like] a felon, so I can’t get a good job. It’s hard for me to get into school,” he said.

“I’ve been so lost. I feel like they took a piece of me that is hard for me to get back.”

The Exoneration Project has helped clear the names of more than 200 people since 2009, including a dozen in Chicago’s Cook County in 2023 alone.

Man convicted of murder sues Chicago police after eyewitness revealed to be blind

A man who spent 12 years in prison for murder is suing Chicago police after being convicted on an eyewitness account from a blind person.

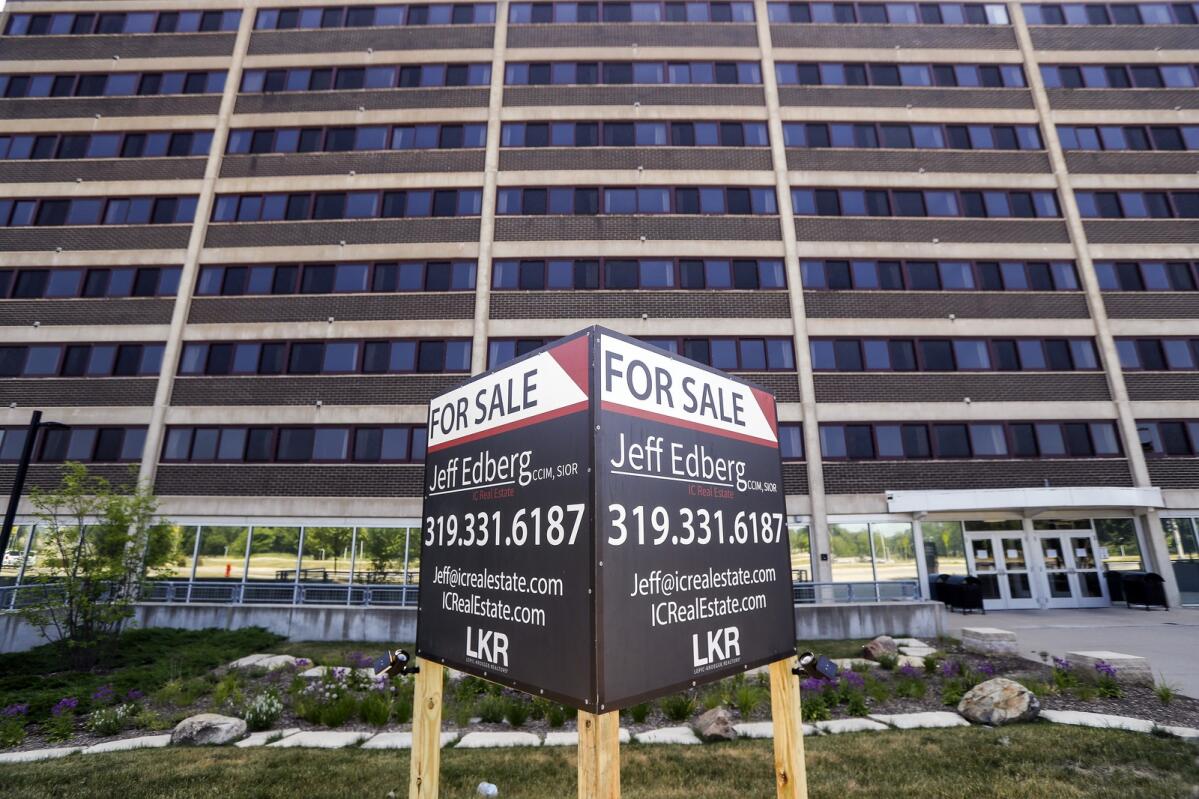

UI Mayflower Hall no longer for sale; cost to live there cut

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 6 Replies

About a year after announcing intentions to shutter and sell its “last-chosen and first-transferred-from” Mayflower Residence Hall, the University of Iowa has taken it off the market — citing “immense interest from returning and prospective students” to live on campus.

“The University of Iowa is not actively marketing Mayflower Hall for sale,” UI Assistant Vice President for Student Life and Senior Director of University Housing and Dining Von Stange said Wednesday. “Based on the future goals for occupancy of the residence hall system by first-year and returning students, we will continue to use Mayflower for student housing.”

A year after listing the 326,000-square-foot property along N. Dubuque Street for $45 million — without landing a buyer — the university in February provided an update on plans to continue using Mayflower for the 2024-25 academic year.

Although the UI in February 2023 suggested Mayflower could close as early as the end of this spring semester, officials also told the Board of Regents at that time that the 2024-25 academic term would be its “final year.”

According to those original plans, selling Mayflower would eliminate maintenance costs and bring in money to help build a new 250- to 400-bed hall for returning students. However, the 56-year-old Mayflower is among the university’s largest halls — housing 1,032 students — and eliminating it from the residence hall rotation would have handicapped the campus’ housing capacity as demand grows.

Although the campus at that time didn’t disclose plans to keep Mayflower in the rotation longer-term — with UI officials telling The Gazette it still planned to sell it — a recent five-year regents report showed expectations UI’s housing capacity would stay level at 6,465 beds between the 2025 and 2029 budget years.

That number is down 88 beds from the 6,553 available in the year that just ended, a result of this summer’s permanent closure of Parklawn Hall — the smallest on campus, featuring suite-style spaces near Hancher Auditorium.

“Parklawn is not highly desired by students and lacks Cambus and food services,” UI officials said. “Since Parklawn Hall is not highly desired by new or returning students and lacks Cambus or food service, UI intends to close it at the conclusion of the current academic year.”

Among the reasons Mayflower — a former apartment complex turned dorm featuring suite-style double rooms that share a kitchen and bathroom — has been less attractive to students is its distance from the main campus and other residence halls. In hopes of increasing its popularity, the UI is adding study spaces and more single rooms, while promoting its privacy for students wanting more independence and its Cambus access.

“Campus leaders are working with students to determine what additional supports and amenities may be offered,” officials said in February.

The university also is cutting the cost to live there.

Instead of the $8,633 charged last year for the standard double with kitchen, bath and air conditioning, the university next year will shave off $560 and charge $8,073 — putting it in line with the standard “double with air” rooms across campus.

“Historically, some students who were assigned there in previous years expressed concern about the cost differential,” Stange said. “This allows all students not to worry about the additional cost of attendance while living in a double room in Mayflower.”

A real estate flyer shows a room inside the Mayflower Residence Hall. The University of Iowa had listed the property for sale at $45 million. (Photo from Lepic-Kroeger, Realtors brochure)

A real estate flyer shows a room inside the Mayflower Residence Hall. The University of Iowa had listed the property for sale at $45 million. (Photo from Lepic-Kroeger, Realtors brochure)

Though the UI has reported an uptick in returning students interested in on-campus living, it didn’t include in its recent five-year residence system report any plans to build that new returning-student hall it proposed last year for the east side of campus, with cost projections between $40 and $60 million.

“The university is always proactively evaluating its housing and dining systems to best serve students who choose to live on campus,” Stange said. “There’s no update to share at this time regarding a new residence hall.”

Mayflower — sitting on 4.1 acres overlooking the Iowa River — is the first thing many UI visitors see as they exit Interstate 80 onto Dubuque Street. Once site of the Mayflower Inn in the 1940s — featuring a popular Mayflower Nite Club — the hangout was razed in the 1960s and replaced in 1968 with the eight-story Mayflower Apartments.

The university started leasing portions of the apartment building in 1979 due to student-housing crowding and bought the building outright in 1983 for a “bargain sale price of $6.5 million.” Mayflower underwent major renovations in 1999 and in again in 2009 after massive flood damage in 2008.

Although the university in 2023 listed the residence hall for $45 million, a recent city property value assessment valued it at $30.7 million.

www.thegazette.com

www.thegazette.com

“The University of Iowa is not actively marketing Mayflower Hall for sale,” UI Assistant Vice President for Student Life and Senior Director of University Housing and Dining Von Stange said Wednesday. “Based on the future goals for occupancy of the residence hall system by first-year and returning students, we will continue to use Mayflower for student housing.”

A year after listing the 326,000-square-foot property along N. Dubuque Street for $45 million — without landing a buyer — the university in February provided an update on plans to continue using Mayflower for the 2024-25 academic year.

Although the UI in February 2023 suggested Mayflower could close as early as the end of this spring semester, officials also told the Board of Regents at that time that the 2024-25 academic term would be its “final year.”

According to those original plans, selling Mayflower would eliminate maintenance costs and bring in money to help build a new 250- to 400-bed hall for returning students. However, the 56-year-old Mayflower is among the university’s largest halls — housing 1,032 students — and eliminating it from the residence hall rotation would have handicapped the campus’ housing capacity as demand grows.

Fall changes

Although the campus at that time didn’t disclose plans to keep Mayflower in the rotation longer-term — with UI officials telling The Gazette it still planned to sell it — a recent five-year regents report showed expectations UI’s housing capacity would stay level at 6,465 beds between the 2025 and 2029 budget years.

That number is down 88 beds from the 6,553 available in the year that just ended, a result of this summer’s permanent closure of Parklawn Hall — the smallest on campus, featuring suite-style spaces near Hancher Auditorium.

“Parklawn is not highly desired by students and lacks Cambus and food services,” UI officials said. “Since Parklawn Hall is not highly desired by new or returning students and lacks Cambus or food service, UI intends to close it at the conclusion of the current academic year.”

Among the reasons Mayflower — a former apartment complex turned dorm featuring suite-style double rooms that share a kitchen and bathroom — has been less attractive to students is its distance from the main campus and other residence halls. In hopes of increasing its popularity, the UI is adding study spaces and more single rooms, while promoting its privacy for students wanting more independence and its Cambus access.

“Campus leaders are working with students to determine what additional supports and amenities may be offered,” officials said in February.

The university also is cutting the cost to live there.

Instead of the $8,633 charged last year for the standard double with kitchen, bath and air conditioning, the university next year will shave off $560 and charge $8,073 — putting it in line with the standard “double with air” rooms across campus.

“Historically, some students who were assigned there in previous years expressed concern about the cost differential,” Stange said. “This allows all students not to worry about the additional cost of attendance while living in a double room in Mayflower.”

‘No update to share’

Though the UI has reported an uptick in returning students interested in on-campus living, it didn’t include in its recent five-year residence system report any plans to build that new returning-student hall it proposed last year for the east side of campus, with cost projections between $40 and $60 million.

“The university is always proactively evaluating its housing and dining systems to best serve students who choose to live on campus,” Stange said. “There’s no update to share at this time regarding a new residence hall.”

Mayflower — sitting on 4.1 acres overlooking the Iowa River — is the first thing many UI visitors see as they exit Interstate 80 onto Dubuque Street. Once site of the Mayflower Inn in the 1940s — featuring a popular Mayflower Nite Club — the hangout was razed in the 1960s and replaced in 1968 with the eight-story Mayflower Apartments.

The university started leasing portions of the apartment building in 1979 due to student-housing crowding and bought the building outright in 1983 for a “bargain sale price of $6.5 million.” Mayflower underwent major renovations in 1999 and in again in 2009 after massive flood damage in 2008.

Although the university in 2023 listed the residence hall for $45 million, a recent city property value assessment valued it at $30.7 million.

UI Mayflower Hall no longer for sale; cost to live there cut

About a year after announcing intentions to shutter and sell its “last-chosen and first-transferred-from” Mayflower Residence Hall, the University of Iowa has taken it off the market — citing “immense interest from returning and prospective students” to live on campus.

Day 1 of recruiting for Anthony Knox

- By Agoodnap

- Iowa Wrestling

- 176 Replies

P5 Schools and NCAA Working Toward the Revenue Sharing Model

- By Eliot Clough

- The Press Box

- 1 Replies

Uh oh? Yay? I don't know what to think.

www.espn.com

www.espn.com

NCAA, Power 5 agree to let schools pay players

The NCAA and its leagues are moving forward with a multibillion-dollar settlement agreement that will allow schools to directly pay players for the first time in the history of college sports.

Any Bee Keepers Here?

- Off Topic

- 13 Replies

Thinking of putting a Hive on my property,I'll be starting with just one unless someone has a great reason. My main focus would be more pollination around the property and enjoying the honey.

Just getting started, with our climate I believe I need a 2 case box and the "super"(?) On top. Anyone have any good brands? ( you can spend 1200 bucks on the "flow" brand, yeesh)

I've read quite a bit about insects that can get into the boxes and it seems being in a full sun environment is my best insecticide( if you will), thoughts on location or things to consider?

Tips and tricks? " if I were just getting started I would put my extra money towards xxxxxxx, it will make life easier" type stuff?

Just getting started, with our climate I believe I need a 2 case box and the "super"(?) On top. Anyone have any good brands? ( you can spend 1200 bucks on the "flow" brand, yeesh)

I've read quite a bit about insects that can get into the boxes and it seems being in a full sun environment is my best insecticide( if you will), thoughts on location or things to consider?

Tips and tricks? " if I were just getting started I would put my extra money towards xxxxxxx, it will make life easier" type stuff?

Hot TV news reporter assaulted while reporting on a mass overdose situation

- Off Topic

- 6 Replies

CHICO (CBS13) — A Chico television news reporter is recovering after someone attacked her while she was broadcasting live on Facebook.

KRCR’s Meaghan Mackey was reporting outside of a home when it happened.

Her station, KRCR, issued the following statement: “Meaghan is very shaken up but is okay. We are thankful law enforcement was right there and handled the situation quickly. We appreciate the kind words so many of you have offered Meaghan tonight.’

Mackey was reporting on a mass drug overdose in Chico. Investigators say a dozen people between 19 and 30 years old overdosed inside a house. One person died, authorities said.

Two officers became sick from exposure to the drug – believed to be fentanyl.

At least seven people remained hospitalized as of Sunday night.

Nearby law enforcement quickly and stopped the attack on Mackey.

In a series of tweets after the attack, Mackey thanked the quick response from officers and the community for showing their support.

“I will not live in fear of doing my job. I value the freedom of the press & will continue to report on the truth and inform the public, even during times of tragedy,” Mackey tweeted.

It’s unclear if anyone was arrested after the attack.

https://sacramento.cbslocal.com/2019/01/13/reporter-attacked-live-facebook/

KRCR’s Meaghan Mackey was reporting outside of a home when it happened.

Her station, KRCR, issued the following statement: “Meaghan is very shaken up but is okay. We are thankful law enforcement was right there and handled the situation quickly. We appreciate the kind words so many of you have offered Meaghan tonight.’

Mackey was reporting on a mass drug overdose in Chico. Investigators say a dozen people between 19 and 30 years old overdosed inside a house. One person died, authorities said.

Two officers became sick from exposure to the drug – believed to be fentanyl.

At least seven people remained hospitalized as of Sunday night.

Nearby law enforcement quickly and stopped the attack on Mackey.

In a series of tweets after the attack, Mackey thanked the quick response from officers and the community for showing their support.

“I will not live in fear of doing my job. I value the freedom of the press & will continue to report on the truth and inform the public, even during times of tragedy,” Mackey tweeted.

It’s unclear if anyone was arrested after the attack.

https://sacramento.cbslocal.com/2019/01/13/reporter-attacked-live-facebook/

Consumer Confidence up, finally catching up to positive jobs and payroll news

- Off Topic

- 2 Replies

US consumer confidence rises in May after three months of declines

Consumer confidence in the U.S. rose in May following three straight months of declines, but Americans remain anxious about elevated inflation and interest rates.

Ramos is soliciting for answers

- By merr6267

- Iowa Wrestling

- 5 Replies

Tony the (currently) Tarheel needs your help with a survey about his alma mater's wrestling program. Unfortunately I didn't have much input this time. I was kind of checked out this year (and I haven't lived in Iowa since 2009).

Login to view embedded media

Login to view embedded media

Should we be saying, “It’s housing, stoopid?”

Remembering Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs, safe shelter ranks high

In Washington, whoever is in charge usually says: “We don’t have that many tools to make things more affordable.” It seems to me that’s probably more true for items in the grocery store than it is for housing.

Maybe. I think that housing is an incredibly complex knot that, as you pull on any one part of it, it becomes tighter. Of course we need more housing. Of course housing costs are historically high, especially for young people. But there is some validity to the fact that it’s an incredibly thorny, difficult problem.

In your draft platform, there were four or five different points, though, that involved attacking the problem of housing costs.

Oh, yeah, it is the number-one problem, particularly for young people. Housing, housing, housing. That’s it. Across the country. Americans are struggling with housing costs, and this disproportionately affects the young. It disproportionately affects the poor, and not only is housing the primary financial problem, but it’s also totally misunderstood — completely misunderstood — and intentionally so.

Is there anybody who you hear in the political world talking about housing in a way that you just feel like: “Yes, that’s a bullseye.”

In Washington, whoever is in charge usually says: “We don’t have that many tools to make things more affordable.” It seems to me that’s probably more true for items in the grocery store than it is for housing.

Maybe. I think that housing is an incredibly complex knot that, as you pull on any one part of it, it becomes tighter. Of course we need more housing. Of course housing costs are historically high, especially for young people. But there is some validity to the fact that it’s an incredibly thorny, difficult problem.

In your draft platform, there were four or five different points, though, that involved attacking the problem of housing costs.

Oh, yeah, it is the number-one problem, particularly for young people. Housing, housing, housing. That’s it. Across the country. Americans are struggling with housing costs, and this disproportionately affects the young. It disproportionately affects the poor, and not only is housing the primary financial problem, but it’s also totally misunderstood — completely misunderstood — and intentionally so.

Is there anybody who you hear in the political world talking about housing in a way that you just feel like: “Yes, that’s a bullseye.”

Ken Burns weighs in on election

Surprise, surprise, he argues for the continuation of democracy.

www.brandeis.edu

www.brandeis.edu

Undergraduate Commencement Address by Ken Burns

Load more

ADVERTISEMENT

Filter

ADVERTISEMENT