The next generation isn’t buying it.

By Peter Sagal

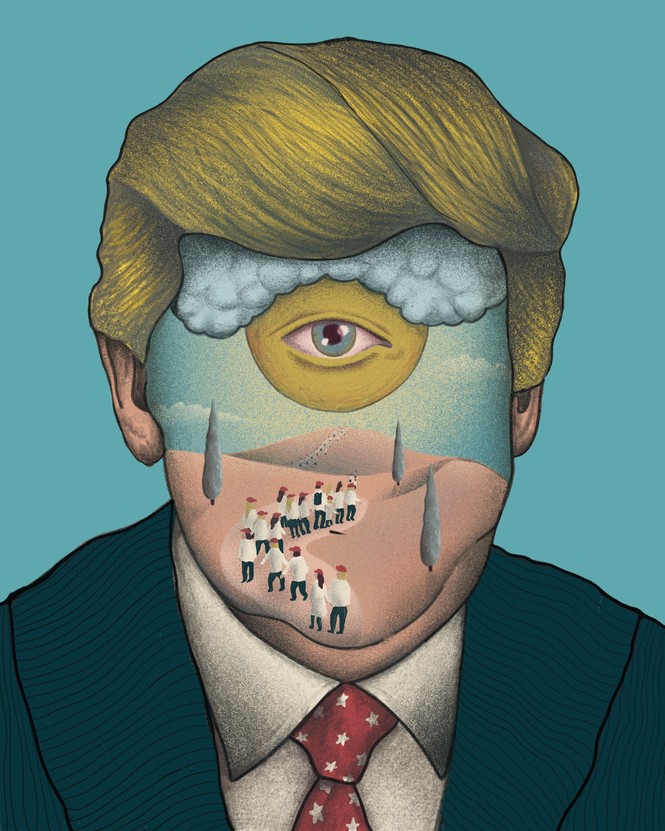

In October of last year, Donald Trump filed a defamation suit accusing CNN of calling him a lot of bad names, the first on the lengthy list being “like a cult leader.” One could assume that Trump would be flattered by that, because cult leaders are usually depicted in pop culture as charismatic masters with near-divine power over the lives of their followers. Jimmy Breslin once called then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani a “small man in search of a balcony.” If so, then Trump is a large man in search of a compound.

He stands in front of massive crowds festooned with insignia proclaiming their allegiance, chanting his name and accompanying him on the familiar refrains: “Lock her/him up!” “Build the wall!” They will countenance no criticism of their idol and accept his version of events without question. The same, of course, can be said about Taylor Swift, although no mob of Swifties has sacked the Capitol. Because she hasn’t asked them to. Yet.

Those who call Trumpism a cult can point to his popularity with Republican voters increasing with each of his four criminal indictments. A CBS poll in late August revealed that the most trusted source of information among those voters—more than conservative media, family members, or clergy—is that famed straight shooter Donald J. Trump.

Peter Wehner: The indictment of Donald Trump—and his enablers

At this point, as the nation faces a series of trials both literal and metaphorical, what label to apply to his movement doesn’t matter. The important question isn’t whether or not Trumpism is a cult. It’s whether the study of cults provides us with any path out of here.

Trump’s suit against CNN was thrown out of court, but Diane Benscoter, the cult expert and former cult member (a “Moonie” of the Unification Church) who compared Trump to a cult leader on CNN, still believes what she said. She’s been working with two incarcerated January 6 participants at the request of their lawyers, not so much to persuade them to recant as to help them with their behavior and attitude while in court—for example, no shouted accusations about the “deep state.” The work is difficult and slow, she told me, even more difficult than her recent efforts to “deprogram” India Oxenberg, one of the high-profile women caught up in NXIVM, the sex cult masquerading as a self-improvement course.

It’s so difficult, in fact, that she sees greater hope in attacking the demand side of cultism, calling for government programs that would treat disinformation and indoctrination as a kind of public-health emergency—a Sanitary Commission of the Mind. If enough people can be taught how indoctrination works, she thinks, they will be able to see it coming for them before it’s too late. Set aside the legal and ethical questions about assigning the government that sort of expansive role; what if it’s already too late? Educating people so they won’t join a political cult, in 2023, is like closing the barn door after the horse has attacked the West Portico of the Capitol with bear spray.

Steven Hassan, another former cult member (also a Moonie), published his book The Cult of Trump in 2019, long before the attack on the Capitol, even before Trump persuaded thousands of his followers to gather indoors unmasked during the worst airborne pandemic in a century. Hassan told me that the MAGA movement checks all the boxes of his “BITE” model of cult mind control—behavior, information, thought, and emotional control. Like all cult leaders, he argues, Trump restricts the information his followers are allowed to accept; demands purity of belief (beliefs that can change from moment to moment, as per his whims and needs); and appeals to his followers through the conjuring of primal emotions—not just fear but also joy.

His rallies, as so many have reported, are ecstatic events; people cheer and laugh as their various enemies are condemned and insulted. Hassan will be the first to tell you that being part of a cult means you’re empowered, special, one of the elect, close to the person who has all the answers/will lead us to paradise/will “make America great again.” That, in fact, may be the greatest disincentive to turn away from Trump: Nothing is more fun than knowing that you and your friends are the ones who are right about everything.

In the four years since the publication of The Cult of Trump, Hassan believes, the movement has gained strength through de facto alliances with other “authoritarian cults” such as QAnon, as well as with groups like the Council for National Policy, a secretive networking organization of powerful conservatives, and the New Apostolic Reformation, a theological movement calling for Christian dominion over politics. The danger is metastasizing, Hassan said, thanks primarily to digital and social media, which take the place of sermons and indoctrination sessions. “We’re on our phones 10 hours a day. People are up all night getting fed YouTube videos,” he said. “You don’t need a compound anymore.”

As cults became more prominent in the 1970s, self-styled “deprogrammers,” paid by desperate family members, would sometimes abduct cult members and keep them isolated and disoriented until they gave up their beliefs. That tended to backfire: What better proof that everyone outside the cult is a dangerous enemy, to a cult member indoctrinated in that belief, than being snatched up and locked in a hotel room? Whether or not the strategy ever worked, it was clearly unethical and even criminal; some deprogrammers served time for kidnapping.

Today it’s clearly not an option: It would take half the country kidnapping the other half of the country, and then who would feed the pets?

On cable TV, liberal pundits offer up regular factual rebuttals to Trump’s claims, as if his followers could be lectured into seeing the truth. But at this point, Trump’s supporters have been with him for up to eight years, through countless scandals, two impeachments, and now four indictments. What facts could anyone possibly conjure that they haven’t heard and dismissed before? Besides, to admit they’re wrong about any one thing would imply that they’ve been wrong the whole time. As anyone who’s been taken in a game of three-card monte and then played again to win their money back will know, the hardest thing in the world to admit is that you’ve been conned.

Instead, Hassan advocates “respectful, curious questioning.” He advised that friends and relatives of those deep in MAGA try reconnecting with them, approaching them without judgment, to remind them of the relationship you had before they turned. Then, through gentle inquisition, ask them to see things from others’ perspectives, to think about occasions when they’ve seen people intentionally misled by others, to ask themselves what it would be like if that happened to them. Eventually—as Hassan said he did, when he was forced by such questions to examine his allegiance to Reverend Sun Myung Moon—they will free themselves from the spell.

Maybe. Diane Benscoter tried just such an approach in a conversation with a right-wing conspiracy theorist named Michelle Queen, on tape for an NPR story in 2021. First, she found common ground by agreeing that harming children is bad. But then:

Diane Benscoter: Some of the things that are being spread about, you know, babies being eaten and things—I don’t think those things are true personally.

Michelle Queen: Um, I do.

At least, as the NPR correspondent Tovia Smith noted, they agreed to keep talking.

To Daniella Mestyanek Young, every group of people has a little cult in it, and every person has a bit of a cult follower within. At 36, and with a master’s in group psychology from Harvard’s Extension School, she’s acquired a following via her series of TikTok videos in which—while furiously knitting—she shares insights from her own history. She was born into the Children of God, which many ex-members describe as a sex cult, and then escaped it to join the U.S. Army, only to find that the Army was kind of a cult too. In her view, all organizations are situated somewhere on the “cultiness spectrum,” and some celebrated groups, such as the military and Alcoholics Anonymous, are much further toward the dark end than you’d like to believe.

In her TikToks, she includes various lists and rules of cults in an ever-present text box above her head, one of which reads:

By Peter Sagal

In October of last year, Donald Trump filed a defamation suit accusing CNN of calling him a lot of bad names, the first on the lengthy list being “like a cult leader.” One could assume that Trump would be flattered by that, because cult leaders are usually depicted in pop culture as charismatic masters with near-divine power over the lives of their followers. Jimmy Breslin once called then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani a “small man in search of a balcony.” If so, then Trump is a large man in search of a compound.

He stands in front of massive crowds festooned with insignia proclaiming their allegiance, chanting his name and accompanying him on the familiar refrains: “Lock her/him up!” “Build the wall!” They will countenance no criticism of their idol and accept his version of events without question. The same, of course, can be said about Taylor Swift, although no mob of Swifties has sacked the Capitol. Because she hasn’t asked them to. Yet.

Those who call Trumpism a cult can point to his popularity with Republican voters increasing with each of his four criminal indictments. A CBS poll in late August revealed that the most trusted source of information among those voters—more than conservative media, family members, or clergy—is that famed straight shooter Donald J. Trump.

Peter Wehner: The indictment of Donald Trump—and his enablers

At this point, as the nation faces a series of trials both literal and metaphorical, what label to apply to his movement doesn’t matter. The important question isn’t whether or not Trumpism is a cult. It’s whether the study of cults provides us with any path out of here.

Trump’s suit against CNN was thrown out of court, but Diane Benscoter, the cult expert and former cult member (a “Moonie” of the Unification Church) who compared Trump to a cult leader on CNN, still believes what she said. She’s been working with two incarcerated January 6 participants at the request of their lawyers, not so much to persuade them to recant as to help them with their behavior and attitude while in court—for example, no shouted accusations about the “deep state.” The work is difficult and slow, she told me, even more difficult than her recent efforts to “deprogram” India Oxenberg, one of the high-profile women caught up in NXIVM, the sex cult masquerading as a self-improvement course.

It’s so difficult, in fact, that she sees greater hope in attacking the demand side of cultism, calling for government programs that would treat disinformation and indoctrination as a kind of public-health emergency—a Sanitary Commission of the Mind. If enough people can be taught how indoctrination works, she thinks, they will be able to see it coming for them before it’s too late. Set aside the legal and ethical questions about assigning the government that sort of expansive role; what if it’s already too late? Educating people so they won’t join a political cult, in 2023, is like closing the barn door after the horse has attacked the West Portico of the Capitol with bear spray.

Steven Hassan, another former cult member (also a Moonie), published his book The Cult of Trump in 2019, long before the attack on the Capitol, even before Trump persuaded thousands of his followers to gather indoors unmasked during the worst airborne pandemic in a century. Hassan told me that the MAGA movement checks all the boxes of his “BITE” model of cult mind control—behavior, information, thought, and emotional control. Like all cult leaders, he argues, Trump restricts the information his followers are allowed to accept; demands purity of belief (beliefs that can change from moment to moment, as per his whims and needs); and appeals to his followers through the conjuring of primal emotions—not just fear but also joy.

His rallies, as so many have reported, are ecstatic events; people cheer and laugh as their various enemies are condemned and insulted. Hassan will be the first to tell you that being part of a cult means you’re empowered, special, one of the elect, close to the person who has all the answers/will lead us to paradise/will “make America great again.” That, in fact, may be the greatest disincentive to turn away from Trump: Nothing is more fun than knowing that you and your friends are the ones who are right about everything.

In the four years since the publication of The Cult of Trump, Hassan believes, the movement has gained strength through de facto alliances with other “authoritarian cults” such as QAnon, as well as with groups like the Council for National Policy, a secretive networking organization of powerful conservatives, and the New Apostolic Reformation, a theological movement calling for Christian dominion over politics. The danger is metastasizing, Hassan said, thanks primarily to digital and social media, which take the place of sermons and indoctrination sessions. “We’re on our phones 10 hours a day. People are up all night getting fed YouTube videos,” he said. “You don’t need a compound anymore.”

As cults became more prominent in the 1970s, self-styled “deprogrammers,” paid by desperate family members, would sometimes abduct cult members and keep them isolated and disoriented until they gave up their beliefs. That tended to backfire: What better proof that everyone outside the cult is a dangerous enemy, to a cult member indoctrinated in that belief, than being snatched up and locked in a hotel room? Whether or not the strategy ever worked, it was clearly unethical and even criminal; some deprogrammers served time for kidnapping.

Today it’s clearly not an option: It would take half the country kidnapping the other half of the country, and then who would feed the pets?

On cable TV, liberal pundits offer up regular factual rebuttals to Trump’s claims, as if his followers could be lectured into seeing the truth. But at this point, Trump’s supporters have been with him for up to eight years, through countless scandals, two impeachments, and now four indictments. What facts could anyone possibly conjure that they haven’t heard and dismissed before? Besides, to admit they’re wrong about any one thing would imply that they’ve been wrong the whole time. As anyone who’s been taken in a game of three-card monte and then played again to win their money back will know, the hardest thing in the world to admit is that you’ve been conned.

Instead, Hassan advocates “respectful, curious questioning.” He advised that friends and relatives of those deep in MAGA try reconnecting with them, approaching them without judgment, to remind them of the relationship you had before they turned. Then, through gentle inquisition, ask them to see things from others’ perspectives, to think about occasions when they’ve seen people intentionally misled by others, to ask themselves what it would be like if that happened to them. Eventually—as Hassan said he did, when he was forced by such questions to examine his allegiance to Reverend Sun Myung Moon—they will free themselves from the spell.

Maybe. Diane Benscoter tried just such an approach in a conversation with a right-wing conspiracy theorist named Michelle Queen, on tape for an NPR story in 2021. First, she found common ground by agreeing that harming children is bad. But then:

Diane Benscoter: Some of the things that are being spread about, you know, babies being eaten and things—I don’t think those things are true personally.

Michelle Queen: Um, I do.

At least, as the NPR correspondent Tovia Smith noted, they agreed to keep talking.

To Daniella Mestyanek Young, every group of people has a little cult in it, and every person has a bit of a cult follower within. At 36, and with a master’s in group psychology from Harvard’s Extension School, she’s acquired a following via her series of TikTok videos in which—while furiously knitting—she shares insights from her own history. She was born into the Children of God, which many ex-members describe as a sex cult, and then escaped it to join the U.S. Army, only to find that the Army was kind of a cult too. In her view, all organizations are situated somewhere on the “cultiness spectrum,” and some celebrated groups, such as the military and Alcoholics Anonymous, are much further toward the dark end than you’d like to believe.

In her TikToks, she includes various lists and rules of cults in an ever-present text box above her head, one of which reads:

Like the other cult experts I spoke with, Young doesn’t believe that anybody can be argued out of Trumpism (or any other firmly held belief). People can save only themselves, as she did. But she argues that such self-rescues are happening all around us.The first rule of cults is:

you’re never in a cult

The second rule of cults is:

the cult will forgive any sin,

except the sin of leaving

The third rule of cults is:

even if he did it,

that doesn’t mean he’s guilty.