Colleges

- American Athletic

- Atlantic Coast

- Big 12

- Big East

- Big Ten

- Colonial

- Conference USA

- Independents (FBS)

- Junior College

- Mountain West

- Northeast

- Pac-12

- Patriot League

- Pioneer League

- Southeastern

- Sun Belt

- Army

- Charlotte

- East Carolina

- Florida Atlantic

- Memphis

- Navy

- North Texas

- Rice

- South Florida

- Temple

- Tulane

- Tulsa

- UAB

- UTSA

- Boston College

- California

- Clemson

- Duke

- Florida State

- Georgia Tech

- Louisville

- Miami (FL)

- North Carolina

- North Carolina State

- Pittsburgh

- Southern Methodist

- Stanford

- Syracuse

- Virginia

- Virginia Tech

- Wake Forest

- Arizona

- Arizona State

- Baylor

- Brigham Young

- Cincinnati

- Colorado

- Houston

- Iowa State

- Kansas

- Kansas State

- Oklahoma State

- TCU

- Texas Tech

- UCF

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Michigan State

- Minnesota

- Nebraska

- Northwestern

- Ohio State

- Oregon

- Penn State

- Purdue

- Rutgers

- UCLA

- USC

- Washington

- Wisconsin

High Schools

- Illinois HS Sports

- Indiana HS Sports

- Iowa HS Sports

- Kansas HS Sports

- Michigan HS Sports

- Minnesota HS Sports

- Missouri HS Sports

- Nebraska HS Sports

- Oklahoma HS Sports

- Texas HS Hoops

- Texas HS Sports

- Wisconsin HS Sports

- Cincinnati HS Sports

- Delaware

- Maryland HS Sports

- New Jersey HS Hoops

- New Jersey HS Sports

- NYC HS Hoops

- Ohio HS Sports

- Pennsylvania HS Sports

- Virginia HS Sports

- West Virginia HS Sports

ADVERTISEMENT

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Filters

Show only:

Gad Saad nails it yet again.

- Off Topic

- 21 Replies

Login to view embedded media

“A society that incorrectly navigates this reality is deep in the abyss of infinite lunacy.

Progressives are poorly calibrated in terms of their empathy.

Illegal migrants > legal citizens

Criminals > victims

Squatters > home owners

Transgender “women” > women

Twerking drag queens > children (for reading hour)

Their entire empathy module misfires.”

“A society that incorrectly navigates this reality is deep in the abyss of infinite lunacy.

Progressives are poorly calibrated in terms of their empathy.

Illegal migrants > legal citizens

Criminals > victims

Squatters > home owners

Transgender “women” > women

Twerking drag queens > children (for reading hour)

Their entire empathy module misfires.”

Conspiracy Theory I made up myself:

- By turkEhawk

- The Press Box

- 0 Replies

In regards to the Hawkeye womens tough draw in the tourney, the NCAA wants to limit the number of games Caitlyn Clark plays. The reason-they don’t want her to build on her already record breaking point total. If she continues to score, her point total will almost certainly be unattainable in the future. The NCAA has the goose that laid the golden egg and they will continue to reap the rewards for the foreseeable future, whether CC is directly involved or not.

However, after she has moved on, and the game becomes ho hum again a few years down the road, they will be looking for another story line to peak interest.

Along comes Juju Watkins! She has already scored more points than Caitlyn as a freshmen! And if she continues that trend (no idea if she will or not) we could be looking at a new mark someday. If she is anywhere close, the NCAA will exploit the feat for all they can get!! So….to make this a possibility, they limit the total that CC attains, and they “manufacture” a new golden goose that they hope will overshadow all their ineptitude!!

Far fetched? Of course it is. But it’s what I do when I have too much free time. And it keeps my mind off of this wrestling season

However, after she has moved on, and the game becomes ho hum again a few years down the road, they will be looking for another story line to peak interest.

Along comes Juju Watkins! She has already scored more points than Caitlyn as a freshmen! And if she continues that trend (no idea if she will or not) we could be looking at a new mark someday. If she is anywhere close, the NCAA will exploit the feat for all they can get!! So….to make this a possibility, they limit the total that CC attains, and they “manufacture” a new golden goose that they hope will overshadow all their ineptitude!!

Far fetched? Of course it is. But it’s what I do when I have too much free time. And it keeps my mind off of this wrestling season

Jennie Baranczyk OU coach former Hawkeye!!

- By StarHawk

- Iowa Men's Basketball

- 7 Replies

I don't think this gets mention enough...or not at all....but Jennie Baranczyk was on coach Bluders first team at Iowa. She played basketball and volleyball I think too. She had a great coaching period at Drake and is now head coach of OU, where she brought that program back to life after Coach Coale had fallen off. Her team this year was Big12 regular season champs after a tough start and hard early schedule. She is great communicator and coach (and recruiter...she got 5* power forward freshman out of Iowa last year in Williams). I'll be rooting for her team as well as Iowa....would have been nice if the slanted committee could have put OU in with Iowa instead of K-st...a team Iowa has faced twice already and committee knows that their huge center gives Iowa problems.

BTW...hope the "Hawkeye from the Storm" podcast folks see this post...so it dawns on them. I heard "Kash" on their make silly comments on OU first game....and no one mentioned Jennie coached them.

BTW...hope the "Hawkeye from the Storm" podcast folks see this post...so it dawns on them. I heard "Kash" on their make silly comments on OU first game....and no one mentioned Jennie coached them.

The top 10 returning linebackers for the 2024 season

- By Digger1

- Iowa Football

- 2 Replies

College Football: The top-10 returning linebackers for the 2024 season | College Football | PFF

LSU's Harold Perkins tops the list of the best linebackers returning to college football in 2024.

3. JAY HIGGINS, IOWA

Higgins was a true ironman for Iowa’s defense, leading all FBS defenders in 2023 with 985 snaps. He still played at an elite level despite practically never coming off the field, finishing fifth among all linebackers in the nation with an 89.6 grade. Higgins ended the year as the most valuable linebacker in the country according to PFF’s wins above-average metric.He always seemed to be around the ball last year, leading the nation with 108 plays where he made first contact on the ball carrier. Higgins was one of only six Power Five linebackers who earned 80-plus grades both as a run defender and in coverage. One of the others is further down this list while the other four are the top-four linebackers on PFF’s 2024 NFL Draft big board: Payton Wilson, Edgerrin Cooper, Junior Colson and Jeremiah Trotter Jr. In fact, Higgins’ 90.8 PFF coverage grade led all Power Five players at the position.

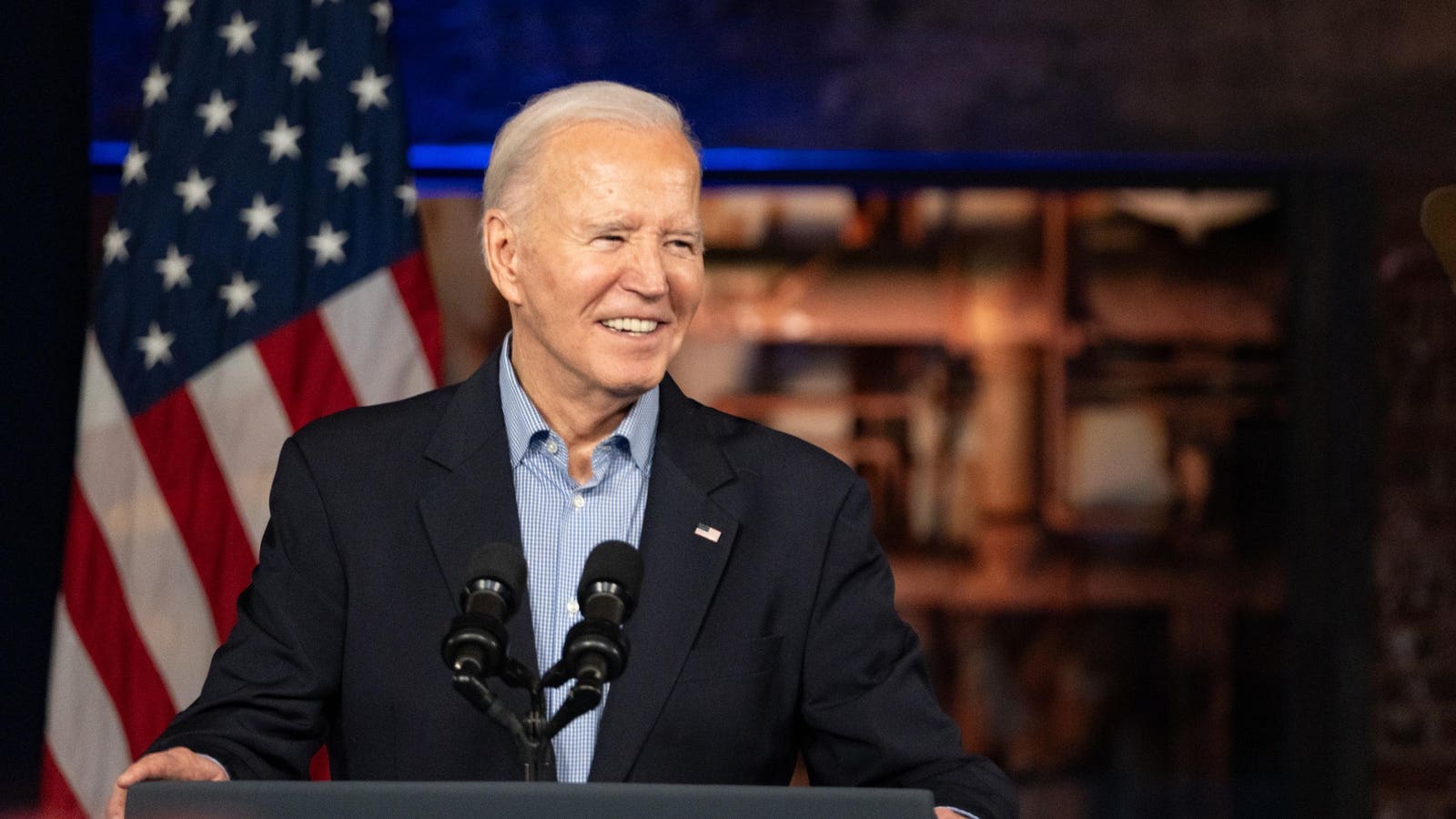

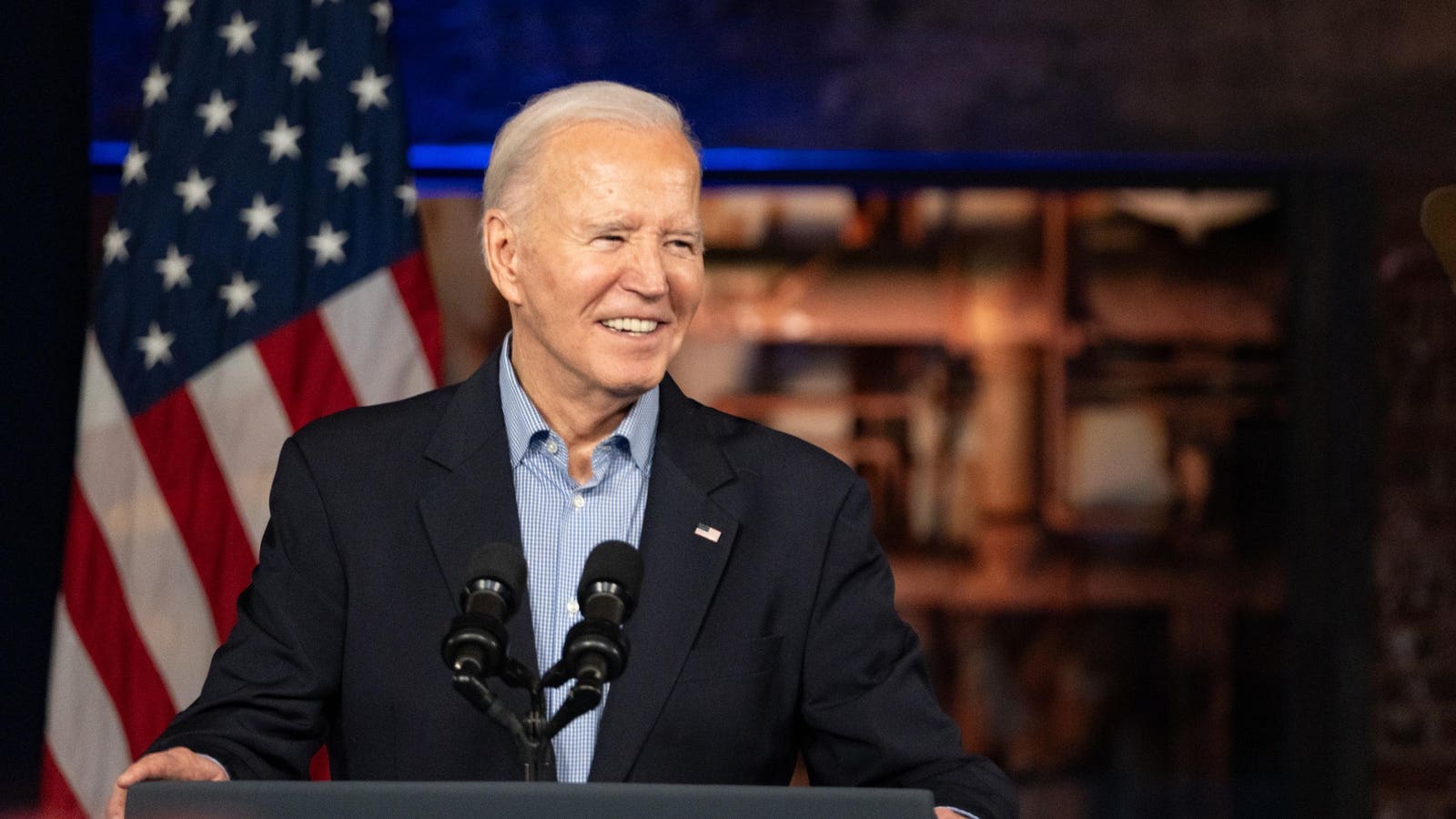

Outside groups pledge to spend $1 billion to reelect Biden

“A new $120 million pledge to lift President Biden and his allies will push the total expected spending from outside groups working to re-elect Mr. Biden to $1 billion this year.

The League of Conservation Voters, a leading climate organization that is among the biggest spenders on progressive causes, announced its plans for backing Mr. Biden on Tuesday, at a moment when his Republican challenger, former President Donald J. Trump, is struggling to raise funds. Mr. Biden’s campaign, independent of the outside groups, expects to raise and spend $2 billion as part of his re-election bid.

Republican groups are likely to spend big ahead of November, as well, but it is difficult to make direct comparisons between the Democratic organizations and their Republican counterparts. Democratic and progressive organizations often announce their spending plans before they have raised the funds, which often come in from small donors. Republican groups that rely more on major donors tend not to telegraph their plans.

The pro-Biden outside money originates from nearly a dozen organizations that include climate groups, labor unions and traditional super PACs. There are left-wing groups like MoveOn and moderate Republicans like Republican Voters Against Trump.”

The League of Conservation Voters, a leading climate organization that is among the biggest spenders on progressive causes, announced its plans for backing Mr. Biden on Tuesday, at a moment when his Republican challenger, former President Donald J. Trump, is struggling to raise funds. Mr. Biden’s campaign, independent of the outside groups, expects to raise and spend $2 billion as part of his re-election bid.

Republican groups are likely to spend big ahead of November, as well, but it is difficult to make direct comparisons between the Democratic organizations and their Republican counterparts. Democratic and progressive organizations often announce their spending plans before they have raised the funds, which often come in from small donors. Republican groups that rely more on major donors tend not to telegraph their plans.

The pro-Biden outside money originates from nearly a dozen organizations that include climate groups, labor unions and traditional super PACs. There are left-wing groups like MoveOn and moderate Republicans like Republican Voters Against Trump.”

Dive Bar Road Trip

How many of these dive bars have you been to? I’ve been to Peacock’s and The Edge. I need to hit a few more of the QC-area bars next time I’m in town.

D1Baseball Weekly Chat: March 18

- By Alum-Ni

- Hawkeye Sports Catch All

- 1 Replies

D1Baseball Weekly Chat: March 18 • D1Baseball

The latest D1Baseball Top 25 Rankings are out and there's a ton of movement this week. We answer your burning questions about the rankings and more.

Again....highlighting any Big Ten or relevant national questions

Chandler: How bout them Huskers? Another series win/sweep against a decent Nicholls team.

Aaron Fitt: Nebraska was one of the first teams out or our Top 25 this year, along with Southern Miss and a few others. I really like Nebraska's body of work -- those are quality series wins at Grand Canyon, College of Charleston, vs. South Alabama and now vs. Nicholls State, which had been 17-3 entering the week an d has a legit Friday night arm. Feels like Nebraska has a chance to wind up being the team to beat in the Big Ten, although I'm not ready to pronounce them the clear favorite. Indiana and Iowa have struggled against very robust early-season schedules, but I think both teams will benefit from all those tests as we get into conference play, and I still think those are probably the two most talented teams in the league. But those two plus Nebraska, Maryland and Rutgers (and possibly even this overvalued Penn State club) all feel like legit contenders for regional bids. Patrick Ebert saw the Huskers this weekend and will have plenty more on the site about them this week.

-----------------------------------------------------

Terp in NC: In your preseason column on the B1G, you went with just two NCAA tourney entrants: Iowa and Indiana. Have you changed your mind on the numbers and specific teams?

Kendall Rogers: Right now, I'm at about 3 or 4 bids for the Big Ten. I feel pretty solid about Nebraska and Maryland at this juncture, and I do feel like either Iowa or Indiana will be a third team. But the question is on a fourth team? Iowa is so far behind the eight ball from non-conference play, but if it rolled throughout conference play, I could see the committee giving them somewhat of a mulligan to some extent for having a very difficult non-conference weekend schedule. I think 4 is your best-case scenario as of TODAY.

-----------------------------------------------------

The Corn Dude: Nebraska is 13-5 with the #2 strength of schedule. Please explain yourselves for not having them in the top 25 this week with four teams exiting.

Kendall Rogers: Corn -- I really like what Nebraska has both in terms of pitching depth and the offensive lineup. I thought the lineup had some impressive balance earlier this year when I saw the Huskers. With that said, if you look at what NU has done on the weekends, I'm not really sure how that's a slam dunk Top 25 team. In the mix? Sure. Slam dunk? Not remotely. But I do think this is a definite regional-caliber club.

Outside Democratic-leaning groups have pledged more than $1 billion to help President Joe Biden’s reelection

- Off Topic

- 14 Replies

Holy balls. This has to be the most lopsided Presidential election $$$ wise, in history. Probably end up a 20-1 advantage in traditional ad time or more.

Outside Democratic-leaning groups have pledged more than $1 billion to help President Joe Biden’s reelection, the New York Times reported Tuesday, giving the incumbent a major fundraising boost as the general election heats up—and as rival Donald Trump reportedly scrambles to raise cash.

The League of Conservation Voters, a climate-focused group, pledged to donate $120 million to Biden’s reelection, the Times reports, putting the fundraising haul by outside groups over the $1 billion mark.

The biggest groups spending money on Biden’s reelection are super PAC Future Forward, the Service Employees International Union and research organization American Bridge, according to the Times, which have pledged between $140 million and $250 million on advertising and other campaign help.

Outside groups—which cannot directly coordinate with the Biden campaign—are likely to raise between $2.5 billion and $3 billion by November, former Emily’s List president Stephanie Schriock predicted to the Times.

The outside spending comes on top of money raised by the Biden campaign and through the Democratic National Committee directly, which reported having $155 million in total cash on hand going into March.

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com

Outside Democratic-leaning groups have pledged more than $1 billion to help President Joe Biden’s reelection, the New York Times reported Tuesday, giving the incumbent a major fundraising boost as the general election heats up—and as rival Donald Trump reportedly scrambles to raise cash.

The League of Conservation Voters, a climate-focused group, pledged to donate $120 million to Biden’s reelection, the Times reports, putting the fundraising haul by outside groups over the $1 billion mark.

The biggest groups spending money on Biden’s reelection are super PAC Future Forward, the Service Employees International Union and research organization American Bridge, according to the Times, which have pledged between $140 million and $250 million on advertising and other campaign help.

Outside groups—which cannot directly coordinate with the Biden campaign—are likely to raise between $2.5 billion and $3 billion by November, former Emily’s List president Stephanie Schriock predicted to the Times.

The outside spending comes on top of money raised by the Biden campaign and through the Democratic National Committee directly, which reported having $155 million in total cash on hand going into March.

Outside Groups Pledge $1 Billion To Biden—As Trump Reportedly Struggles To Fundraise

The Biden campaign and DNC also had $155 million in cash going into March.

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com

Tickets for future NCAA Championships

- Iowa Wrestling

- 9 Replies

Anyone know a reliable way to get good tickets in the Iowa section for NCAAs (not this year’s, but, say, Philly ‘25)?

Thanks and go hawks!

Thanks and go hawks!

New 2026 Rivals250

- The Press Box

- 2 Replies

The 2026 class ranking has been expanded from 100 players to a full Rivals250: https://n.rivals.com/prospect_rankings/rivals250/2026

Ten highest debuts: https://n.rivals.com/news/rivals-rankings-week-ten-highest-ranked-debuts-in-the-rivals250

Adam Gorney goes position-by-position: https://n.rivals.com/news/tuesdays-with-gorney-new-2026-rivals250-released

Ten highest debuts: https://n.rivals.com/news/rivals-rankings-week-ten-highest-ranked-debuts-in-the-rivals250

Adam Gorney goes position-by-position: https://n.rivals.com/news/tuesdays-with-gorney-new-2026-rivals250-released

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson raises eyebrows with comment that First Amendment 'hamstrings' government.

Ya, that's kind'a the point.

www.foxnews.com

www.foxnews.com

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson raises eyebrows with comment that First Amendment 'hamstrings' government

During Supreme Court arguments challenging the Biden admin's alleged coordination with Big Tech, one justice's comments about the government’s relationship with the constitution raised eyebrows.

Clark Shooting Mechanics Analysis

- By Mohawkeye

- Iowa Men's Basketball

- 2 Replies

Interesting read on her mechanics and training.

apple.news

apple.news

What makes Caitlin Clark the best shooter in college basketball? The physics behind her shot — The Athletic

Engineers, her trainer and researches break down why the Iowa star is among basketball's best shooters.

What's with all the fighting?

- By BonzoFury

- Iowa Men's Basketball

- 43 Replies

Seems like there's quite a bit more physical stuff breaking out in college basketball, especially the women's game. Anybody else noticed this? It can't simply be more exposure. I think there's a trend. Is it merely a reflection of society in general...bad officiating...coaching?

What say you?

What say you?

State controlled media

- By biggreydogs

- Off Topic

- 27 Replies

Yes, it Was an Insurrection

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 1 Replies

By

Aaron Blake

Senior reporter

July 13, 2021|Updated yesterday at 3:51 p.m. EDT

There are many ways in which former president Donald Trump and his allies have used the passage of time and fading memories to call into question the true narrative of Jan. 6. They have suggested it wasn’t really Trump supporters storming the Capitol. They’ve said it looked more or less like a “normal tourist visit.” They’ve surmised based upon faulty logic that maybe the FBI was actually responsible for it. And most recently, they’ve begun pitching Ashli Babbitt as a martyr (despite few saying that when the video of her being shot circulated almost instantly).

But perhaps the most persistent revisionism involves that word most often used to describe the events of that day: “insurrection.” The idea that this word doesn’t actually apply epitomizes and neatly sums up the argument that the media and Democrats have oversold this whole thing to make Trump look bad.

The problem with that argument, of course, is that the word most definitely does apply.

This blog recapped the building insurrection-doubter movement a month ago, and it has only picked up steam since then. Fox News host Tucker Carlson regularly uses the word in sarcastic scare quotes. A significant chunk of House Republicans continue to vote against legislation honoring the Capitol Police that uses the word. Trump family members and top allies frequently promote social media users casting doubt on the “insurrection.” Trump attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani even said this week that Babbitt’s death has been used to “make it into an insurrection.”

As with Babbitt, it’s worth noting how little this resembles how Republicans initially talked about the events of that day. In fact, both the GOP leaders of the House and the Senate, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) and Sen. Mitch McConnell (Ky.), used the term early this year. Trump impeachment attorney Michael van der Veen also conceded at Trump’s trial, “The question before us is not whether there was a violent insurrection of the Capitol. On that point, everyone agrees.”

Not so much anymore, it seems.

The argument that this wasn’t an insurrection generally boils down to one or more of a few points: the lack of more weapons, the ragtag crew that stormed the Capitol, the failure in overturning the election results, and the fact that it ended within a few hours.

The thing is, though, that none of these really bear on whether it was an insurrection.

Merriam-Webster defines insurrection as “an act or instance of revolting against civil authority or an established government.” The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “an organized attempt by a group of people to defeat their government and take control of their country, usually by violence.” West’s Encyclopedia of American Law defines it as “a rising or rebellion of citizens against their government, usually manifested by acts of violence.”

Even if you somehow accept that the Capitol riot wasn’t as violent as some made it out to be — which, I mean, we have the video evidence, and there were multiple deaths and tons of injuries — it clearly included large-scale violence. There needn’t be hundreds of people with guns or other arms for it to be an insurrection.

Nor do these definitions carve out exceptions for failed or even poorly executed efforts to thwart or replace a government. It doesn’t matter that many of these people were old or hapless, as Carlson and other pundits often emphasize.

Some critics of the insurrection doubters have pointed to Sideshow Bob’s quip on “The Simpsons” in which he said, “Attempted murder? Now honestly, what is that? Can you win a Nobel Prize for attempted chemistry?” But this is actually more clear-cut than that. Insurrection loops in both failed and successful efforts; a successful one is generally also regarded as a revolution or a coup d’etat. That this didn’t reach that level and perhaps never could have doesn’t mean it wasn’t an insurrection. Nor do these definitions require any kind of sustained revolt.

One could seemingly quibble with whether one aspect of the Cambridge definition applies: “an organized attempt.” But this was certainly organized at least to some extent, as many of the indictments lay out in detail and as the bipartisan Senate report lays out in discussing the missed warning signs. Just because some people might have been swept up in the moment and didn’t take part in organizing themselves or were bad at organizing doesn’t mean there wasn’t organization. What’s more, organization is a broad term that could seemingly even be read to include the actions of those who incited others.

What unites all of these definitions is in what the actions are directed against: the government. The reference works cite actions taken “against civil authority or an established government,” “to defeat their government and take control of their country,” and “against their government.” That’s what made this not just a riot, but also an insurrection. There was an effort to change control of the government by force — the government two weeks hence, yes, but all the same.

The insurrection doubters have also cried hypocrisy because “insurrection” was not used last summer to describe racial justice protests that turned violent. But the vast, vast majority of those supposed “insurrections” involved no effort to directly target government officials, nor were they aimed at defeating or violently forcing the replacement of an established government. One can argue that the violence in those protests was glossed over too much, perhaps, but an “insurrection” isn’t defined by the level of violence; it’s defined by its purpose.

And that’s why a term that is rarely applicable to such violent scenes is most definitely applicable here. Just because it feels too severe to you and you believe it connotes something closer to Napoleon and Fidel Castro than 60-year-old Richard “Bigo” Barnett doesn’t mean Barnett didn’t engage in an insurrection.

Aaron Blake

Senior reporter

July 13, 2021|Updated yesterday at 3:51 p.m. EDT

There are many ways in which former president Donald Trump and his allies have used the passage of time and fading memories to call into question the true narrative of Jan. 6. They have suggested it wasn’t really Trump supporters storming the Capitol. They’ve said it looked more or less like a “normal tourist visit.” They’ve surmised based upon faulty logic that maybe the FBI was actually responsible for it. And most recently, they’ve begun pitching Ashli Babbitt as a martyr (despite few saying that when the video of her being shot circulated almost instantly).

But perhaps the most persistent revisionism involves that word most often used to describe the events of that day: “insurrection.” The idea that this word doesn’t actually apply epitomizes and neatly sums up the argument that the media and Democrats have oversold this whole thing to make Trump look bad.

The problem with that argument, of course, is that the word most definitely does apply.

This blog recapped the building insurrection-doubter movement a month ago, and it has only picked up steam since then. Fox News host Tucker Carlson regularly uses the word in sarcastic scare quotes. A significant chunk of House Republicans continue to vote against legislation honoring the Capitol Police that uses the word. Trump family members and top allies frequently promote social media users casting doubt on the “insurrection.” Trump attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani even said this week that Babbitt’s death has been used to “make it into an insurrection.”

As with Babbitt, it’s worth noting how little this resembles how Republicans initially talked about the events of that day. In fact, both the GOP leaders of the House and the Senate, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) and Sen. Mitch McConnell (Ky.), used the term early this year. Trump impeachment attorney Michael van der Veen also conceded at Trump’s trial, “The question before us is not whether there was a violent insurrection of the Capitol. On that point, everyone agrees.”

Not so much anymore, it seems.

The argument that this wasn’t an insurrection generally boils down to one or more of a few points: the lack of more weapons, the ragtag crew that stormed the Capitol, the failure in overturning the election results, and the fact that it ended within a few hours.

The thing is, though, that none of these really bear on whether it was an insurrection.

Merriam-Webster defines insurrection as “an act or instance of revolting against civil authority or an established government.” The Cambridge Dictionary defines it as “an organized attempt by a group of people to defeat their government and take control of their country, usually by violence.” West’s Encyclopedia of American Law defines it as “a rising or rebellion of citizens against their government, usually manifested by acts of violence.”

Even if you somehow accept that the Capitol riot wasn’t as violent as some made it out to be — which, I mean, we have the video evidence, and there were multiple deaths and tons of injuries — it clearly included large-scale violence. There needn’t be hundreds of people with guns or other arms for it to be an insurrection.

Nor do these definitions carve out exceptions for failed or even poorly executed efforts to thwart or replace a government. It doesn’t matter that many of these people were old or hapless, as Carlson and other pundits often emphasize.

Some critics of the insurrection doubters have pointed to Sideshow Bob’s quip on “The Simpsons” in which he said, “Attempted murder? Now honestly, what is that? Can you win a Nobel Prize for attempted chemistry?” But this is actually more clear-cut than that. Insurrection loops in both failed and successful efforts; a successful one is generally also regarded as a revolution or a coup d’etat. That this didn’t reach that level and perhaps never could have doesn’t mean it wasn’t an insurrection. Nor do these definitions require any kind of sustained revolt.

One could seemingly quibble with whether one aspect of the Cambridge definition applies: “an organized attempt.” But this was certainly organized at least to some extent, as many of the indictments lay out in detail and as the bipartisan Senate report lays out in discussing the missed warning signs. Just because some people might have been swept up in the moment and didn’t take part in organizing themselves or were bad at organizing doesn’t mean there wasn’t organization. What’s more, organization is a broad term that could seemingly even be read to include the actions of those who incited others.

What unites all of these definitions is in what the actions are directed against: the government. The reference works cite actions taken “against civil authority or an established government,” “to defeat their government and take control of their country,” and “against their government.” That’s what made this not just a riot, but also an insurrection. There was an effort to change control of the government by force — the government two weeks hence, yes, but all the same.

The insurrection doubters have also cried hypocrisy because “insurrection” was not used last summer to describe racial justice protests that turned violent. But the vast, vast majority of those supposed “insurrections” involved no effort to directly target government officials, nor were they aimed at defeating or violently forcing the replacement of an established government. One can argue that the violence in those protests was glossed over too much, perhaps, but an “insurrection” isn’t defined by the level of violence; it’s defined by its purpose.

And that’s why a term that is rarely applicable to such violent scenes is most definitely applicable here. Just because it feels too severe to you and you believe it connotes something closer to Napoleon and Fidel Castro than 60-year-old Richard “Bigo” Barnett doesn’t mean Barnett didn’t engage in an insurrection.

Mother who left baby at home for 10-day vacation gets life for murder

- By cigaretteman

- Off Topic

- 5 Replies

An Ohio woman whose toddler died after she left her at home to go on a 10-day vacation last summer has been sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Kristel Candelario, 32, pleaded guilty last month to the aggravated murder of her daughter, 16-month-old Jailyn. Prosecutors said she left the toddler alone in a playpen in their Cleveland home in June while she traveled to Detroit and Puerto Rico.

When she returned from her trip, she found Jailyn unresponsive and called police, according to the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office. She changed her child’s clothes before emergency responders arrived and pronounced her dead shortly thereafter.

The toddler was “extremely dehydrated” at the time of her death, prosecutors said, and medical examiners determined that she had died of starvation and dehydration. She weighed 13 pounds — about seven pounds less than what was recorded at her last doctor’s visit about two months prior, Elizabeth Mooney, the deputy Cuyahoga County medical examiner, told the court Monday.

County Common Pleas Court Judge Brendan Sheehan said the toddler’s death “wasn’t simply an oversight” and told Candelario she had several opportunities to intervene and save her daughter’s life.

“You committed the ultimate act of betrayal, leaving your baby terrified, alone, unprotected, to suffer what I’ve heard was the most gruesome death imaginable, with no food, no water, no protection,” he said. He also accused Candelario of having showed “no remorse.”

In court Monday, he compared Candelario’s life sentence to the confinement her daughter must have suffered before her death.

“The only difference will be that prison will at least feed you and give you liquids that you denied her,” he said.

Candelario also has an older daughter. It’s unclear where she was at the time of her mother’s vacation in June.

Her attorney, Derek Smith, did not immediately respond to a request comment. At her sentencing, he said Candelario had suffered from depression and mental health issues, although she was ruled fit to stand trial.

“There’s no justification for her actions,” Smith said, calling it the “absolutely worst parenting imaginable.” He insinuated that treatment she received for mental and physical problems before June had been insufficient.

Candelario addressed the judge and the court Monday, saying that Jailyn’s death has caused her “so much pain” and that she hopes her parents and daughter will forgive her.

“I am not trying to justify my actions, but nobody knew how much I was suffering and what I was going through,” she said, through a Spanish interpreter.

Kristel Candelario, 32, pleaded guilty last month to the aggravated murder of her daughter, 16-month-old Jailyn. Prosecutors said she left the toddler alone in a playpen in their Cleveland home in June while she traveled to Detroit and Puerto Rico.

When she returned from her trip, she found Jailyn unresponsive and called police, according to the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor’s Office. She changed her child’s clothes before emergency responders arrived and pronounced her dead shortly thereafter.

The toddler was “extremely dehydrated” at the time of her death, prosecutors said, and medical examiners determined that she had died of starvation and dehydration. She weighed 13 pounds — about seven pounds less than what was recorded at her last doctor’s visit about two months prior, Elizabeth Mooney, the deputy Cuyahoga County medical examiner, told the court Monday.

County Common Pleas Court Judge Brendan Sheehan said the toddler’s death “wasn’t simply an oversight” and told Candelario she had several opportunities to intervene and save her daughter’s life.

“You committed the ultimate act of betrayal, leaving your baby terrified, alone, unprotected, to suffer what I’ve heard was the most gruesome death imaginable, with no food, no water, no protection,” he said. He also accused Candelario of having showed “no remorse.”

In court Monday, he compared Candelario’s life sentence to the confinement her daughter must have suffered before her death.

“The only difference will be that prison will at least feed you and give you liquids that you denied her,” he said.

Candelario also has an older daughter. It’s unclear where she was at the time of her mother’s vacation in June.

Her attorney, Derek Smith, did not immediately respond to a request comment. At her sentencing, he said Candelario had suffered from depression and mental health issues, although she was ruled fit to stand trial.

“There’s no justification for her actions,” Smith said, calling it the “absolutely worst parenting imaginable.” He insinuated that treatment she received for mental and physical problems before June had been insufficient.

Candelario addressed the judge and the court Monday, saying that Jailyn’s death has caused her “so much pain” and that she hopes her parents and daughter will forgive her.

“I am not trying to justify my actions, but nobody knew how much I was suffering and what I was going through,” she said, through a Spanish interpreter.

Everyone playing in a Bracket Challenge?

- Iowa Men's Basketball

- 0 Replies

Curious, if there an Iowa Group? I liked it a lot when this site had its own challenge a few years ago.

Load more

ADVERTISEMENT

Filter

ADVERTISEMENT